David and Goliath…

by Robin Cox, Human Planet Cameraman

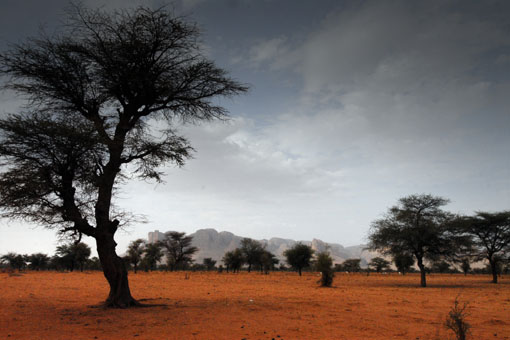

Mamadou is our “David”. He’s only sixteen, with a small but strong frame, delicate features and a gentle demeanour. He is perfect for the role. Our Goliath is an elephant, a bull, one of a herd of desert elephants that share with Mamadou the watering hole of Banzena on which they both depend for survival in Mali’s arid Sahel desert. His arsenal is just a small handful of sticks.

A year ago Mamadou met his Goliath in a pitched battle on the shore of the lake. Having been without water for two days, his herd of fifty cows were gagging for a drink but the elephants had got there first, and they were not going to move aside. What followed in the moments afterwards we fortuitously captured on film. It was not the story we planned for the shoot, but it was perfect. Immediately after the battle was won, Mamadou and his cattle had drunk their fill and man and cows vanished back into the Sahel. Unbeknown to him, our “David” had been cast, and a mission had begun to seek him out and film more of his story. A search was launched across the many small nomadic settlements scattered over miles and miles of desert. A photo of our wanted man was presented at each stop and finally, after three days, he was found. Unfortunately, though not surprisingly, he was terrified, and he went into hiding for fear that he might be in trouble for his stick missile attack on the elephants. He was soon found again, reassured and eventually talked into letting us tell his tale.

I am here in Mali a year later to finish the sequence. Not present on the original shoot, I am introduced to Mamadou. Like many we have left behind around the world, he has become pretty well versed in the techniques of film making and now, having been able to see the previous year’s results, he is beginning to comprehend what on earth it is that we are trying to achieve. He knows that when I (the cameraman) say “speed” and the director says “action” it means that he should be doing something. Whether or not we have succeeded in conveying adequately what that something should be is another matter! Most of all he knows that hearing the phrase “just one last time” means it will probably not be the last time and it will most likely be ages before we are happy with the shot.

Generally we communicate without words and I act things out or use crude signs… faster, slower, closer, quieter, gentler. It’s a source of constant amusement for all. Much of the communication between us is by facial expression alone. Amusement, bemusement, anger, frustration, exhaustion and a myriad of other feelings are almost always clear to see in each others faces, with no need for translation. These things are universal. With these aids and cheeky smiles, we’ve got to know each other, and had some fun in the searing heat, sandstorms and mud.

Mamadou is in many ways as civilised a young man as you are likely to meet, gracious, kind, and intelligent. He carries himself with dignity despite a life spent in the desert living a nomadic herder’s life which I can only really describe as “old testament”. However he is wholly uneducated, quite unwashed and crudely dressed. Despite all this he is just as much a modern man as any one pacing the streets of London - just without all the gab, garments and gadgets.

On many occasions I have had the notion that I recognise something peculiarly familiar in a person, a characteristic, an inflection in the voice, sometimes combined with a facial expression, and it is like déjà vu. Today I realised that Mamadou is reminding me of someone. As he’s the only African cattle herder I know it’s not somebody just like him, but it is somebody just like him. There’s a theory, so I was once told, that there are only twelve (or was it twenty?) character types in the world. It’s rather simplifying things I know, and I don’t think anyone has ever successfully catalogued them, but my experiences this year of meeting so many far flung strangers have often borne it out. And Mamadou is reminding me of someone.

This sort of thing happens a lot, yesterday for example…. We’re out in the desert looking for lake-bound elephants when Meddi, our local Mali elephant expert, speaks to us through the door of the car. His gun is slung over his shoulder, he’s wearing a long cotton gown and a blue turban, his skin is dark, coarse and leathery from the relentless sun, he looks, and is, utterly exotic. As I listen to the conversation, ears half closed and not understanding hardly a word, I suddenly realise he reminds me so much of an old acquaintance from London, a Glaswegian red-headed accountant. I recognise him absolutely as being just like him, both the same type, and suddenly I know him so much better. Of course, the appearance of the two men could not be more different, but they share the same somewhat glazed look in their eyes, they have the same uncertain smile and both speak with a soft but deliberate tone. Their physiques are even alike, as though their flesh has grown upon their character, they are both lean and stringy. In so many ways they could be brothers.

This phenomenon has happened many times in the past few years with Human Planet and other projects. I have met a Nepalese porter who is just like my Wiltshire builder, hunted whales in Indonesia with a man much like my uncle Malcolm, met a tribal wife in India who reminds me of a nun from my convent school days and fixed fog nets with a Chilean man who reminds me of Pavarotti! I’ve begun to seek out the likenesses. First I recognise something familiar, sometimes instantly, sometimes gradually, then I rifle through the people I know, and have known and try to find the link. With no visual reference I hold up their characteristics in my mind like a photo, seeking out the person in my nomadic life who I know is just like them, though sometimes they fail to come to mind, like a forgotten tune. I am still working on Mamadou, but I know I know someone else just like him and I’m sure he won’t be a cattle herder.