The Original Jungle and its Mighty Beasts

By Rachel Kinley, Assistant Producer of Human Planet

The word Jungle itself comes from the Sanskrit word for forest. It was in this original jungle, on the borders between India and Burma, that we filmed people working with one the most iconic of jungle animals – the forest elephant.

It took us three days and several forms of transport, including a rickety old logging truck, to reach the camp which would be our home for the next two weeks. There wasn’t just us staying there though, this camp was home to a dozen elephants and their mahouts.

We were there to film them moving felled trees from the forest, as part of a sustainable logging business. Watching the elephants at work was so impressive. They are powerful beasts who can move a massive log as if it was a tiny twig. Amazing!

Being so strong, they really intimidated me at first. After we’d filmed with them for a while though, I realised that that their mahouts were well in control of these animals. So, when I was offered the chance, I jumped at the opportunity to take one for a ride. I was only allowed to travel on the female elephants so as not to spook the bulls. Our cameraman Robin however was game to ride any elephant any which way, and even learnt how to steer it along with his feet!

Spending time with these mahouts who dedicate their lives to looking after these animals was an empowering experience. This sequence really shows that the Human Planet Jungles programme isn’t just about living in rainforests, it’s about the incredible relationships people have with their environment and the species which live within.

The Human Planet Jungles and Grasslands episode can be seen on the Discovery Channel.

Music Planet: Andy Kershaw Keeps His Head

by Roger Short, Producer, Music Planet , BBC Radio 3

In March this year, on his first trip for Music Planet, presenter Andy Kershaw visited the Solomon Islands. This was the most remote area either of us had ever been to, so we decided we really should find some people – and music – that were as far away from western culture, particularly the influence of the Christian missionaries, as possible. So we took a small plane to a grass runway on Malaita Island, drove in a truck for two hours, took a boat along the coast for an hour, and finally reached a village of the Kwaio people. Even here a church and a school awaited us. But after a three-hour steep trek up a mountain, we arrived at the remote Kwaio villages which still follow animist culture. They weren’t exactly geared up for visitors, so our team of five (including engineer James Birtwistle, plus local guide and interpreter) all slept together in a tiny hut on stilts. Dinner was a cauldron of boiled potatoes. Fortunately the music more than made up for it.

First we heard the music of the ‘gilo stones’ – two players with bamboo sticks in hands and feet, knocking them on smooth stones in complex rhythmic patterns that Steve Reich would be proud of. Then the head of the village sat in a circle with four other men, gently beating out a rhythm with sticks, and first humming, then chanting an epic song. They later told us it was about the murder of a former British Governor who had tried in vain to impose taxes on the Kwaio. Andy asked them if they were former head-hunters. They queried the word ‘former’ – ‘we do reserve the right’, the chief said, ‘if it became necessary…’ No further challenging questions were asked.

Dale Templar, Human Planet, Series Producer says:

I can’t wait to listen to “Music Planet”. It is the BBC Radio 3 sister series that will accompany “Human Planet” when it transmits in the UK early in 2011. The Music Planet” team have been travelling around the world recording music from people all the different environments we have been to on the main series but in some cases they have visited different tribes and groups of people.

Music Planet

by Roger Short, Producer, BBC Radio 3

The Music Planet team – engineer James Birtwistle, Andy Kershaw and producer Roger Short – look at the wrong camera while on the job in Papua New Guinea

Yes indeed, as Andy Kershaw tells us on his promo video, filmed recently in Papua New Guinea, he and Lucy Duran are currently travelling the globe for a new eight-part series of world music programmes. Music Planet will be a companion series for BBC One’s major new natural history project Human Planet, presenting the music of some of the cultures featured in the TV series.

As I write, Andy is on his way to Thailand, there to join producer James Parkin and engineer James Birtwistle for a trip that includes Laos and Burma; tomorrow Lucy Duran and I, with engineer Martin Appleby, head off on a rather shorter haul to Galicia in northern Spain - this is for a feature on how the local traditions are influenced by music from across the sea (and did you know there was a mass migration of Britons buying villas in northern Spain in the sixth century, bringing Celtic culture to that part of the world?).

Just as Human Planet shows how people relate to their landscape and environment, in Music Planet, we’re showing how all this is reflected in the local music. So far Lucy has visited Madagascar, Kenya, Greenland and Mali, and Andy has been to the Solomon Islands as well as Papua New Guinea. There’s plenty more before the series broadcasts early next year. If you’re interested, we’ll let you know how we get on…

David and Goliath…

by Robin Cox, Human Planet Cameraman

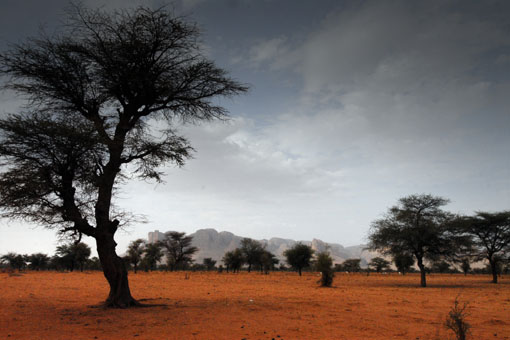

Mamadou is our “David”. He’s only sixteen, with a small but strong frame, delicate features and a gentle demeanour. He is perfect for the role. Our Goliath is an elephant, a bull, one of a herd of desert elephants that share with Mamadou the watering hole of Banzena on which they both depend for survival in Mali’s arid Sahel desert. His arsenal is just a small handful of sticks.

A year ago Mamadou met his Goliath in a pitched battle on the shore of the lake. Having been without water for two days, his herd of fifty cows were gagging for a drink but the elephants had got there first, and they were not going to move aside. What followed in the moments afterwards we fortuitously captured on film. It was not the story we planned for the shoot, but it was perfect. Immediately after the battle was won, Mamadou and his cattle had drunk their fill and man and cows vanished back into the Sahel. Unbeknown to him, our “David” had been cast, and a mission had begun to seek him out and film more of his story. A search was launched across the many small nomadic settlements scattered over miles and miles of desert. A photo of our wanted man was presented at each stop and finally, after three days, he was found. Unfortunately, though not surprisingly, he was terrified, and he went into hiding for fear that he might be in trouble for his stick missile attack on the elephants. He was soon found again, reassured and eventually talked into letting us tell his tale.

I am here in Mali a year later to finish the sequence. Not present on the original shoot, I am introduced to Mamadou. Like many we have left behind around the world, he has become pretty well versed in the techniques of film making and now, having been able to see the previous year’s results, he is beginning to comprehend what on earth it is that we are trying to achieve. He knows that when I (the cameraman) say “speed” and the director says “action” it means that he should be doing something. Whether or not we have succeeded in conveying adequately what that something should be is another matter! Most of all he knows that hearing the phrase “just one last time” means it will probably not be the last time and it will most likely be ages before we are happy with the shot.

Generally we communicate without words and I act things out or use crude signs… faster, slower, closer, quieter, gentler. It’s a source of constant amusement for all. Much of the communication between us is by facial expression alone. Amusement, bemusement, anger, frustration, exhaustion and a myriad of other feelings are almost always clear to see in each others faces, with no need for translation. These things are universal. With these aids and cheeky smiles, we’ve got to know each other, and had some fun in the searing heat, sandstorms and mud.

Mamadou is in many ways as civilised a young man as you are likely to meet, gracious, kind, and intelligent. He carries himself with dignity despite a life spent in the desert living a nomadic herder’s life which I can only really describe as “old testament”. However he is wholly uneducated, quite unwashed and crudely dressed. Despite all this he is just as much a modern man as any one pacing the streets of London - just without all the gab, garments and gadgets.

On many occasions I have had the notion that I recognise something peculiarly familiar in a person, a characteristic, an inflection in the voice, sometimes combined with a facial expression, and it is like déjà vu. Today I realised that Mamadou is reminding me of someone. As he’s the only African cattle herder I know it’s not somebody just like him, but it is somebody just like him. There’s a theory, so I was once told, that there are only twelve (or was it twenty?) character types in the world. It’s rather simplifying things I know, and I don’t think anyone has ever successfully catalogued them, but my experiences this year of meeting so many far flung strangers have often borne it out. And Mamadou is reminding me of someone.

This sort of thing happens a lot, yesterday for example…. We’re out in the desert looking for lake-bound elephants when Meddi, our local Mali elephant expert, speaks to us through the door of the car. His gun is slung over his shoulder, he’s wearing a long cotton gown and a blue turban, his skin is dark, coarse and leathery from the relentless sun, he looks, and is, utterly exotic. As I listen to the conversation, ears half closed and not understanding hardly a word, I suddenly realise he reminds me so much of an old acquaintance from London, a Glaswegian red-headed accountant. I recognise him absolutely as being just like him, both the same type, and suddenly I know him so much better. Of course, the appearance of the two men could not be more different, but they share the same somewhat glazed look in their eyes, they have the same uncertain smile and both speak with a soft but deliberate tone. Their physiques are even alike, as though their flesh has grown upon their character, they are both lean and stringy. In so many ways they could be brothers.

This phenomenon has happened many times in the past few years with Human Planet and other projects. I have met a Nepalese porter who is just like my Wiltshire builder, hunted whales in Indonesia with a man much like my uncle Malcolm, met a tribal wife in India who reminds me of a nun from my convent school days and fixed fog nets with a Chilean man who reminds me of Pavarotti! I’ve begun to seek out the likenesses. First I recognise something familiar, sometimes instantly, sometimes gradually, then I rifle through the people I know, and have known and try to find the link. With no visual reference I hold up their characteristics in my mind like a photo, seeking out the person in my nomadic life who I know is just like them, though sometimes they fail to come to mind, like a forgotten tune. I am still working on Mamadou, but I know I know someone else just like him and I’m sure he won’t be a cattle herder.

Elephants in the Jungle

by Mihali Moore, Camera Assistant

I thought I had been to remote places in the past, but this trip proved that there is always somewhere further and more isolated than you think. Two flights, a long drive across politically unstable territory, a choice of a four hour trek through jungle or a three hour trip on a rickety truck. An experience that we were told (and can confirm) was like your shirt going through a tumble dryer with you still wearing it! Having trekked for a few hours, it was getting dark and the sound of the truck was music to our ears - or so we thought! After ten seconds of driving aboard, I instantly regretted it. It was terrifying. I lost count of the times I thought it was going to tip over. Perhaps the chap next to me had the right idea. Reeking of whiskey, I don’t think he was worried about anything. Luckily the truck got stuck near the camp and we gladly walked the last twenty minutes by foot. The truck would later be rescued by our pachyderm friends and brought to its final destination.

Nonetheless we arrived safe and sound in the evening to the camp that would be our home for the next two weeks. Our fixer had done an impressive job. We found a selection of individual tents with camp beds, cooking equipment, tables, lights and even power sockets in each one. Mod cons in the deep jungle. Not bad at all!

The next day we met some of the elephants for the first time and carried out a recce of the area for filming spots. I had never been this close to these animals before and was instantly struck by their majestic grace. Wary of our presence, you could tell they knew something was up. We also had the pleasure of meeting the elephant contractor. With his penchant for whiskey and the way the others behaved around him, it was clear he wanted to be perceived as the boss. During our numerous encounters with him, we would find ourselves having to respect his customs and offers of whiskey, whilst listening to his thoughts on what the world would be like without water?!? On the subject of water, it had started to rain. Monsoon season was round the corner and the chances of nicely backlit elephants working in harmony were looking slim.

It was amazing to see how these creatures worked. They can understand up to 65 commands and push heavy logs around as if they were twigs. Each elephant has its own mahout, a young man who perches atop the elephant and ‘drives’ him. Using commands and pressure with their feet, the mahout can direct, steer and command the elephant at a remarkable pace. Keeping up with them wasn’t easy and it’s clear that using the elephant is the only way to get the job done. Ramprashad was our main elephant and he was an impressive size. Whilst slightly apprehensive of us at first, he soon warmed to us and even let us ride him for a bit. In fact all the elephants seemed to accept us quite quickly. At one point I remember standing on a track in a melee of elephants that were trying to push a laden truck up a muddy slope. All I could see was wrinkly skin. I looked at Robin Cox, our cameraman, (to whom I was tethered). He was breathing in deeply and arching his back, desperately trying to fit into a gap between the dense jungle face and an elephant’s belly.

What I found remarkable is the mutual understanding between the mahout and elephant. The elephant will only work for a few hours and if it doesn’t want to do something it quite simply will not. The mahout diligently washes and feeds him each day, which strengthens the bond between the two of them. Each evening the elephant is released into the jungle to roam free. The next day the mahout must look for the animal, which, despite its freedom, won’t have gone far. The chains go on and the elephant knows it’s back to work, a true example of beast and man working in harmony. It was a real privilege to see this unique and rare tradition in action. You’ll get to get to see the reason why we were filming this partnership in 2011. Hopefully we provided a good story for the series!

A Cameraman’s View

by Toby Strong, Freelance Cameraman with Deserts/Grasslands Team

Mongolians, Bushmen, Dorobo and Tubu.

Minus fifty degrees to plus fifty degrees.

Hunters, dancers, herders and traders.

Helicopters, hot air balloons, horses and dug outs.

The last couple of years have given me a breadth and depth of experience that as a young boy I couldn’t have dreamed of.

Thanks to the faith of the grasslands and deserts team I have hunted kudu in the Kalahari; soared over camel trains crossing the Sahara; run on foot towards feeding lions; chased wolves on camel back and caught snakes in a canoe. I’ve danced through the night with the Wodaabe, followed a bird to raid a honey comb and rounded up 2,000 cattle by chopper.

To film all this all this I’ve had toys, lots of toys! (of the highly technical variety)…

Macro lenses, long lenses, time lapse, underwater cameras, infra-red cameras, cameras in helicopters, cameras on rafts, cameras on quad bike, horse back and camel back. Cranes, tracks, jibs, steadicams and hot air balloons.

I’ve travelled to some of the most remote corners of the planet and returned with amazing memories and a few exotic diseases. We managed to knock down a teensy weensy part of a sixth century fort, discovered a carpet viper up my shorts, crashed our balloon and got chased out a hide by a leopard.

Compared to some of the Human Planet shoots, a walk in the park.

So what will I take away from filming on this unique series? Apart from the obvious amazing experiences it will be the shared sense of trying to do something very special with the incredible Human Planet team.

While every tribe I’ve worked with has their own unique and special way of life , I have found two common links between everyone - humour and kindness.

I feel humbled and honoured to have worked on this series and with such wonderful people.

Dale Templar, Series Producer

What Toby is talking about here is common humanity. While making this series we have tried to celebrate the similarities and differences in all of us and I really hope this is played out when people watch the series.

Slip Sliding in Ladakh

by Robin Cox, freelance cameraman, Human Planet

Snow covered our footsteps as we retreated from Pidmo. It had been snowing on and off for a week, the flat roofs of every mud brick house were thick with it and the residents acknowledged our departure as they shovelled their rooftops.

Three days earlier we had advanced downstream on the frozen Zanskar river from Zangla, a mere 8.5km, with the intention that we would progress further the next day to begin our filming. The Chadar, or “sheet” as the iced river is known in winter, had proved to be in poor shape that day. Sections of solid ice gave way frequently to slushy margins and became impassable so we had to resort to the river banks, ploughing through waist deep snow. It was exhausting in the extreme, no step ever finding a sound footing. Two of our heavily laden porters had been ekeing out every bit of open ice when they overwhelmed the thin crust and crashed through. Climbing out, soaked to the skin, they marched on before they froze. No surprise then, that on our arrival at Pidmo morale was low.

The week’s snow had wrecked the length of the Chadar, a hundred avalanches had swooped down onto the ice, puncturing the river’s skin and damming its flow. The pressure then built beneath the surface of the ice and blew huge holes in the ice sheet, as though a giant’s fist had struck it. Water had flooded over the ice, flushing loose shards down stream till they piled up like flotsam against the snowy dam. Some less fortunate than us had been walking on the river when the avalanches occurred. One man, a worker building a new road in the valley, was trapped under an avalanche and sadly perished; others had been forced to wade up to their waists through the icy flood waters to reach safety.

Our mission was to film eleven children and seven fathers as they walked the six day trek along the frozen river from Zangla, a 4000m high mountain village in the Zanskar region of the Tibetan Plateau. Their destination the town of Leh, where the children were being returning to school after the winter holiday. This yearly pilgrimage is routine for the people of the area. The Chadar forms a seasonal highway through stunning gorges, allowing relatively easy access out of the mountains, impossible by road during the winter months when the mountain passes are closed by snow. It is usually traversed without great difficulty and we ourselves had walked upstream on smooth firm ice just a week before with smiles on our faces. The river had been alive with local people marching in both directions, carrying goods of all kinds.

We had been told that in living memory there had been no deaths in avalanches and only two deaths due to drowning when the ice had given way in the spring. We had felt confident that our return trip would be just as easy. To be extra cautious we had left an extra week to make it down the river well before the end of February when traditionally the ice begins to melt and the Chadar becomes perilous. This year the un-seasonal snow had changed everything, and it began to seem as if our film was ill-fated.

Now we found ourselves in retreat - a great caravan of fifty porters carrying our 600Kg of film kit, camping gear and supplies. Days earlier when we started optimistically from Zangla, we had begun to hear the bad news… ‘the worst Chadar I have ever seen’ said one local when we arrived in Pidmo and dissent began to spread through our porters. A meeting was held with the fathers and guides while the porters had their own out in the snow, a shop stewards meeting of a kind. The consensus was not good, nobody was willing to go further so a retreat back to Zangla was the only option.

The river was torturously hard going so we walked on the road, relentlessly trudging in deep snow, navigating a path by telegraph poles, a beaten army returning from battle. The 8.5km took an aching six and a half hours; it was last light as we clawed our way into Zangla and back up the steps of Stanzin’s house, one of the fathers with whom we were staying. We collapsed - the altitude and snow had pushed us to the extreme. Too breathless to talk, David the director asked me to phone the producer, Mark Flowers, back in the UK to let him know of our retreat. Over the next 24 hours a plan to evacuate by helicopter formed and we contemplated abandoning the film.

There was only one chance to save the situation. The fathers told us that given a good spell of clear cold weather, just maybe the ice would heal and we could try again. We decided to sit it out. Next morning the sun shone in a deep blue sky. Hopes were raised and rescue postponed. One clear day followed another as we eagerly awaited news of an arrival from downriver that would signify it was once more passable. We played ball with Stanzin’s daughter and son, Dolkar and Chosing, on the rooftop whilst our guides kept an eye on the distant river. We washed our stinking thermals and waited… but no-one came.

Fears grew that the Chadar was finished for the year. We were washed around in a sea of consternation, trying to find a way to rescue the film before we were evacuated. Finally we formed a plan: we would film with just Stanzin and his two children walking as far as they could before being forced to turn back by the obstacle that lay somewhere downstream… at least we would have something to show for our toil. So three days after returning beaten to Zangla we set out once more for the river. We followed the trail of a snow-plough clearing the route to the road builders’ camp to bring home the dead worker’s body. Like a funeral procession, we followed the rattling machine to the ramshackle camp; the atmosphere in the camp was sobering. The porters again began to lose heart and more negotiations followed. Having successfully talked them round, we set out early the next morning.

It was icy cold, -30C, a bitter but sweet climate in light of our prayers for the Chadar to be safe. We clambered over the avalanches in silence, spread out to minimise risk, and advancing as fast as we could to get past the east facing slopes before the heat of the rising sun caused further falls. By lunchtime we had arrived safely back on the frozen river. The section we found ourselves on seemed solid enough, but as we ventured downstream the havoc the avalanches had wrought on the river became obvious, and there were still monumental obstacles out of sight for still no-one appeared from downstream. We filmed for two days, making the most of the weather until we reached a pool of open water only negotiable by means of clambering over a narrow rocky ledge. What seemed impossible for us to negotiate, seemed a breeze for the kids, but we felt we could go not go further with our equipment and returned to camp for the night. It seemed our story was over, all that remained to do were a few shots the following morning and then we would retreat to await the airlift. We had done our best in the circumstances.

I awoke the next morning to the familiar sleeping bag, iced by my night’s breath. There was much chatter in the camp and the chef was singing and shouting, which was not unusual, but there was a good vibe in the air. We gradually surfaced, squeezing into our rock hard boots and many thermal layers. Nick, the sound recordist, (always first into the mess tent for hot tea with chef) was greeted by good news. Max, David and I joined him and heard it too. That morning, at the crack of dawn, two men had arrived from down river, they had made it, the ice was apparently back, rough in places but sound and passable… suddenly our story was saved. Later that morning, twenty-one days after leaving Leh, we began to walk the Chadar to school with Dolkar, Chosing and Stanzin and the real film began. I have never known such a roller coaster of a shoot, or ever been away so long and achieved so little with the very real prospect of coming home empty handed.

We reached the school in Leh on the last day of the holidays and proudly sent Dolkar in her crisp new uniform with her brother through the school gates to begin their new term. Mission complete, we headed for the comfort of a hotel. Father Stanzin turned on his heel to start the return trip back to Zangla. He was only halfway through his journey, but as usual he took it in his stride.

Life is all about packing cases

by Jasper Montana, Technical Coordinator

Metal pins are slowly spreading across the map of the world in our office – each one representing a trip, a recce, a shoot, and another sequence of Human Planet recorded onto what have now become many kilometres of magnetic video tape. For each of us on the Human Planet team, each pin represents a different moment of time.

For those who went on location, it may be a life changing adventure, a harrowing experience, or a drop in the ocean. For those left in Bristol or Cardiff, it might be a sigh of relief as the crew depart, a moment of pause in a quiet office, or a stressful planning process which lingers long after the crew depart, when phone calls from the Jungle require a mortally wounded shoot to be remotely stitched back together.

On many occasions the pin represents for me long days of getting a plethora of filming equipment squeezed into the smallest possible cases for transport to location. So I was going to write a post about how the human desire to make order out of chaos can be summed up in the line ‘life is all about packing cases’ but I thought I’d just make a time-lapse video instead.

Enjoy.

Packing cases for a shoot to Algeria - timelapse video coming soon

Only a handful of pins are left in the jar – who knows what each has in store.

Singing in the Rain

by Mark Flowers, Producer/Director Rivers/Urban team

The most heart-stealing and downright soul- enhancing benefit of working on a Human Planet shoot is the children we encounter while we are filming. It’s unbelievably refreshing to step outside of a regulated, fast-paced and impersonal modern, urban society and meet people who live in a more open, communal and for me personally, a far more “Human” way.

The children we met during our trip to film living root bridges in one of the most remote areas of North-East India were fantastic - cheeky, smart and funny.

To the young people who live in isolated hill villages in the rainforests of Meghalaya, the arrival of a gangly bunch of giant, pale-skinned strangers, brandishing weird black boxes, screens and cables, was the most surprising thing to happen in a long while. The circus had come to town!

Within minutes of us stepping out of the cars, there were bright eyes at the windows and small hands waving from the homes we passed. High pitched “hellos” echoed all around while tiny toddlers stood dumb struck for a few seconds in doorways and then exploded into howls. Dogs barked and sulky, caged cuckoos crooned from dark corners.

Whenever we set up to film very quickly we were surrounded in a small lava flow of children, far to shy to talk to us individually, but en masse, well that’s different, isn’t it? Whenever we got the camera out we were mobbed!

- Smiling to camera

The funny thing was that we were hoping to shoot short stories for our sister production, working title “Little Human Planet”, showing how children live in different parts of the world. This depended on the little people we were hoping to film behaving as if the camera wasn’t there: Fat- chance!

We soon realised that if we were to get any shots that looked even vaguely natural, the crowd of children needed to be distracted, and that meant entertaining them. Guess who had to do the entertaining: Me. Yikes!

Just so you know I am a greying man in early middle age. I am not a totally serious person but as a director on location I have a role to play out, a reputation to maintain. I have to be seen to be in charge! Usually you’d find me in earnest conversation with the team, or looking sternly down my monitor checking that each shot is right.

Singing in the rain

I didn’t have a white rabbit, I don’t know any tricks, so the only thing I could think of to do instantly was to sing! it was raining too , I had an umbrella – so I started with “I’m singing in the rain” but soon moved on to nursery rhymes to keep the “show” on the road.

I am not sure if the footage of the crowd and the children will end up being used as everyone looks very surprised or is laughing, but the most magical thing is that the little children joined in with me. Incredibly in such a remote part of the world they knew “Baa Baa black sheep” and “Twinkle Twinkle little star”! The memory of singing in the rain with little children holding technicolour parasols is a memory I will always cherish.

Here is a clip. Unbeknown to me, Richard our cameraman turned the movie camera on me and caught me during my act. Enjoy!

[bbc-bc video=21316429001]

Cold hands, crazy cranes and frozen fish

Bethan Evans, Researcher

by Bethan Evans, Researcher, Arctic/Mountains team

As the “cold” researcher for the Arctic programme of Human Planet last month I was lucky enough to find myself in a tiny village on the West Coast of Greenland. With our small crew we were in search of the elusive Greenland shark, known to Greenlanders as Eqalussuaq It’s one of the largest sharks in the world and the only species living in Arctic waters. The Greenland shark lives in deep water, rarely seen near the surface, preferring the frigid cold at depths of up to 2000 metres. As the sea ice melts, local fishermen start seeking it out and we wanted to film their search.

Filming in the Arctic winter is incredibly tough, that’s without the prospect of trying to film an elusive shark that is particularly camera shy! Try passing the cameraman delicate lens tissue and filters while wearing three pairs of gloves. If you do risk taking them off, your fingers freeze to the filters’ cold metal casing.

Or try to keep your crew happy at lunch when their sandwiches have frozen into a solid block!

But throw in a camera crane and an inventive crew and the frozen fun really begins! In order to get some great shots of our fishermen, Amos and Karl-Frederik (a father and son team), we decided to set up the crane over an ice fishing hole. They were busy fishing there for halibut, before turning their attention to sharks.

A useful find

The crane works on a counter-balance system so we had planned ahead and hired gym weights from the nearest town. Unfortunately we didn’t have quite enough weight, making the crane difficult to manoeuvre. We scoured the bare, white landscape desperately looking for something to use as a weight. Eventually one of the crew spied a hapless frozen fish which had been lying next to an old fishing hole for days. In Inuit culture every part of a caught animal is used, so in true Arctic spirit we decided this fish would be put to use.

Tipping the balance

The large and quite frankly extraordinarily ugly fish was hauled off the ice and heaved into our medical emergency bag. The bag was emptied of all life-saving equipment to make way for Freddie the Fish. Happily the fish, after a bit of modification, was just the right weight to balance the crane and we carried on filming, much to the amusement of the Greenlandic fishermen.

Karl-Frederik and Amos in polar bearskin trousers

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

And finally…..

It’s been another busy month on Human Planet. Our Deserts team are just about to leave for Mali to film a fascinating story about elephants. It is always difficult trying to keep up with the crew in the field in these remote locations . We spend lots of time struggling with Sat phones, as satellites move away and break signal at the crucial moments. “You want a Doctor?…” Crackle , splat…10 minutes later as another satellite cares to drift into sat phone sight lines and we are all ready to contact the BBC Health and Safety Department… “Oh! You want Doctor Who recorded, no worries” . However, when I spoke to director Nick Brown from high in the Ethiopian mountains recently, he sounded as clear as a bell . It must have had something to do with being so close to those satellites!

Dale Templar, Series Producer

A Grass Calendar

Jane Atkins, Researcher, Deserts/Grasslands team.

A waving white flag is usually a sign for peace, but in the Omo valley it was quite the opposite. In a vast valley of green grasslands and leafy trees these bright flags stood out as bold signs announcing that a violent stick fight was being planned between two villages. It was these incredible stick fights, or Dongas that we hoped to film - but finding out exactly when they would happen was a bit trickier! With only a ten day shoot in this massive valley that stretched to Sudan, we had to find out when each Donga was taking place, and if the chiefs of each village were happy for us to film.

White flags waving

Luckily we were working with Zablon Beyene, an incredible person and wonderful fixer, who introduced us to wise old chiefs and proud confident warriors with smiles.

Zablon and I share our umbrella

Over a 5 day recce we walked through villages and valleys to meet Suri elders, sat under shady trees in the heat of the day to talk to young fighters, and sketched out a badly drawn and dusty map of which villages were planning Dongas.

Sitting on the grass, with my map in my dirty hands, we just needed to mark it according to our western agenda of time. Diary planning and meeting deadlines becomes second nature in TV, but here dates were less clear, even to Zab! When we asked the chief when the Donga would happen he picked a long stem of grass, and with dark, leathered hands and tied evenly spaced knots. He explained how each knot represented one day, so the grass stalk handed to us with 8 knots meant the Donga would be on the 8th day. With slight apprehension I translated the dates onto my map, and thanked the chief. Now, after hundreds of handshakes and Suri meetings, all that remained was getting the camera crew to the right location.

The knotted rope calendar

On the morning of the Donga we walked to the clearing - it was silent, except for the sound of hundreds of dragonflies buzzing around in the sun! 2 hours later, with all our camera kit ready and a crane rigged, we looked at the empty clearing and hoped we’d got the right day after all!

We heard the men coming before we saw them; chants and songs through the trees, getting louder as they approached. Then gun shots! This, Zablon told us, was just guys firing shots into the air to psych themselves up. It worked, as the air was suddenly filled with excitement and adrenaline, as hundreds of men poured into the clearing, waving their sticks. As the crowd circled two posturing fighters, they stabbed a white flag into the ground; the donga had started.

To set the scene our cameraman Mike Fox moved the crane 20 feet into the air to reveal an amazing image of hundreds of men in combat - a scene you’ll never see any where else. We filmed all day, with the crane, then moving hand held amongst the crowds and spectators, and also with an incredible high speed HD camera that captured the force of each fighter. Moving through pumped up crowds, dodging swiping sticks, and ducking from celebratory gun shots were part of the experience and chances we took to film the sequence.

As I led a cameraman into another position I was mistakenly hit by one stick, and as I ran for a new battery I heard the whizzing of a gunshot past my head! The brutality of the Donga really did separate the men from the boys, and was a fascinating insight to the Suri world. As we packed up I was happy that all our planning had paid off, but even happier that we’d all survived!