Living with Lions

by Jane Atkins, Human Planet Researcher

‘You see, Lions and the Dorobo, we feed each other.’

‘If we hunt a large animal, we take away as much as we can, but leave the rest for the lions to feed on. And sometimes the lions kill a really fat animal and we say, lets take this one. It is not simple, you have to track carefully and quietly. You are scared.. thinking - will I be mauled?’

‘But when you are hungry and know lions have killed first - you take your chance. There are days when we eat only what the lion has killed. We live on those lion kills until we finally make our own kills.

When we filmed 3 Dorobo hunters stride up to 15 lions to steal from their fresh kill our hearts were in our mouths. Courageous? Ingenious? Suicidal? All of these perhaps, but this one act is undeniably impressive. The Dorobo say they are hunters just like lions. They watch lions, and how they hunt. Just as lions do, the Dorobo watch every animal on the great plains - and study each individual. Like lions they observe which ones are wounded, slower, easier to pick off. They wait and wait until the time is right to hunt. And if the lion gets there first, well the Dorobo turn that into another opportunity.

There are three lion prides living in the same area as the Dorobo. This 22 strong pride are just a few hundred metres from the Dorobo's regular camp.

But these opportunities are fading, and fast. These hunting and scavenging practices may be age old, but in 21st Century Kenya, they are banned under the country’s blanket law that no hunting is allowed in Kenya. Although the law was made primarily for big game hunters, it has been enforced at the local level, with traditional tribes, to avoid any ‘grey’ areas.

And so these Dorobo men are living a daily struggle of holding onto a lifestyle passed down through the generations; being free to walk through the great plains, hunt game to feed themselves and their family and sleep under the stars in caves and hidden valleys. Now, they all accept that although they were brought up to be hunters, they will not be bringing up their children to be hunters, to know the wildlife as intimately as they do.

Olkinyei is one of the last pockets in Kenya where the Dorobo still live, but in the last year, the area has been identified as a new conservancy, which means a step up in wildlife conservation in the area. This will ultimately push out of the Dorobo hunters.

And so in our lifetime, we will see an end to this ancient lifestyle of hunting, gathering and scavenging. An accumulative knowledge that has been passed down over 1000s of years.

In a time when stories about endangered wildlife regularly hit the headlines, few people seem to notice that incredible human cultures are being lost; ‘like swatting a mosquito - no-one seems to notice’. The irony here is that wildlife conservation has played a strong part in the Dorobo’s fate.

Whether you think this is right or wrong, it seems the fate for the Dorobo is inevitable. However, it may still be possible to keep their extraordinary tracking skills alive.

Today Jackson Looseyia, who runs a safari lodge in the Masaai Mara, has started employing Dorobo men to be spotters and trackers for his tourists. Jackson says, ‘If the Dorobo way of life disappears, so too does their knowledge. The Dorobo can spot and name any distant bird or animal, identify any nearby track or noise, and tell the story of hunt through reading the tracks in the sand.’

So perhaps this is one way for Rakita and his friends to keep their knowledge alive, even if their traditions die. It may not be as heart racing as hunting a buffalo, listening to the sounds of the night, or stealing food from a lion, but perhaps it’s enough? Rakita told me as we left ‘Of course I am sad to say goodbye to the life of my father, my grandfather… but what can I do? I cannot continue this life much more… I have already been in prison before now! And to bring up my son as a hunter here would be irresponsible. I don’t want him to go to prison. It is a shame, but what can I do?’.

If Human Planet achieves anything, a respectful salute to some of the people we filmed with would be a great thing. For the team back in the UK, finding some of these unique stories was hard, and filming them was challenging. But in a few years to come, these stories may turn out to be the last record of not just the Dorobo but many of the other people and cultures we were so privileged to film.

Watch the Dorobo steal from the lions here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pNeNTMmltyc

THE BBC COMES TO THE ‘OUTBACK’

by Phil O’Brien, Fixer

My name is Phil O’Brien and I live in a place called the Northern Territory of Australia. It’s a place you can wind your clock back a few years, have a beer, and live in peace. Spectacular, panoramic and wild, it’s a huge area, and there’s way more cattle live there than people.

I suppose I’ve lived a bit of a gypsy life drifting from job to job, and had my share of adventure and also a little misadventure in this great place. Everything from catching crocodiles to trying my hand at being a drink waiter… and everything in-between. But not so long ago, I got roped into one of the most exciting rewarding experiences of my life, and I’ll never forget the day the BBC film crew came to the ‘Outback’.

The phone rang with a sharp electrified burst, directly over my left ear, was way too early for a bloke that had been drinking beer after beer, some short hours before. Somehow I got the phone to my ear and answered.

The BB who? BB what…eh, excuse me?

Well, the sweet melodic voice of charming BBC Researcher Jane Atkins never missed a beat. ‘We need a ‘Fixer’ she politely announced. Now me being still half cut and not understanding film terminology, did what any respectable citizen of the Northern Territory would have done…hung up and went back to sleep.

During the next few days Jane Atkins followed up with more calls and information, dedicated and relentless in her pursuit of organising the film shoot, which had to be in the heart of Northern Territory cattle country. I tried to explain that Territory cattle country can be hard, merciless and unforgiving …and that was on a good day! But Jane Atkins stuck to her guns, and wanted me to help organise something that was going to be bigger than Ben Hur. What an honour! This wasn’t going to be no ordinary Mickey Mouse documentary, the BBC wanted to get right down in the bulldust and cow dung and film a rip roaring helicopter cattle muster in one of the world’s last frontiers.

It was a big ask, but Jane Atkins had come to the right man.

I knew just about every bloke, every horse, and every anthill in the Northern Territory. I knew that when it comes to cattle, one man had risen to the top and in a tough environment that breeds tough men, that’s no mean feat.

Big bustling ‘Ben Tapp’ was no ordinary legend.

Built like a brick toilet block, Ben Tapp liked to sprinkle horse shoe nails on his muesli…. he knew no fear. Ben Tapp was one hundred percent pure Territory cattleman, and when I told Jane he also flies a helicopter like a man possessed, the stage was set. Ben Tapp took no convincing, he always knew he was a larger than life character and it was only a matter of time before he hit the big screen.

The day finally came and the BBC film crew landed at our humble airport in the Territory capital of Darwin. What a fantastic bunch of people, I thought to myself as the introductions flowed and the pommy accents filled the air. They were a star studded line up, the best in their field. Jane Atkins was even better looking in real life than I imagined and the cameraman was a friendly bloke called Toby Strong. Accompanying them was the director, charming Susan McMillan, and technical assistant and roustabout, Jasper Montana. Sound man Ian Grant who flew in from Queensland. After a flurry of baggage, camera and sound kit, hire cars and groceries, we headed off on our 600 kilometre journey down to Maryfield Cattle Station, home of the legendary Ben Tapp.

Right from the start I really liked their humility; there was no big egos, no pretence, just a great film crew chomping at the bit. Keen to roll it, wrap it, and get it in the can.

We broke our journey after about 300 kilometres at Katherine, just in time to witness a fairly lively punch up between a couple of locals at the petrol station. The BBC film crew weren’t too fussed, they’d been all over the world, and two bantam weights swinging like rusty gates weren’t about to freak them out. Next stop down the track a bit was the one horse town of Mataranka, population 200 [including cattle].

The BBC was starting to get hungry so I steered them over to the Pub. Inside there were people propped up drinking furiously. It was like ‘God’ had personally just rung the pub and told them the world’s ending in half an hour, so get into it. In amongst it all was the publican, a glamorous lady called Deb, wandering around in a beautiful flowing gown, quite a sight in amongst all the rough necks. I introduced her to the BBC film crew. If she’d had a red carpet she would have rolled it out but instead she cooked a great feed of Barramundi and chips for everyone, she was a great host.

With Barra and chips hanging off our ribs we made the last few hours to Maryfield Station and finally everyone had a chance to meet Ben Tapp. It was all very warm, and although Ben is tough, hard, wild and all the rest of it, he is also a very generous bloke, and he totally opened up his house and his property to the BBC film crew, and nothing was going to be too much trouble. Ben’s hospitality really was first class. He was right on the ball, he had 2000 head of cattle to muster and he had his young team of stockmen fully briefed. His right hand man on Maryfield was a bloke called Rankin Garland who also was a gifted chopper pilot. Right from the start everyone really hit it off.

Back Row(from left) Warick Field[Cineflex Camera Operater

The next ten days for me were just unreal, I got to see a world class film crew in action and I was totally inspired. Camera man Toby Strong went from sun up to sundown and still had energy, I remember one time he was hiding in a bush filming cattle as they filed passed, a snake came out of nowhere and slithered over his leg, but he never flinched, he just kept filming. There was no stopping him, where ever the action was, there was Toby.

Susan McMillan was a great director and she brought the best out in everyone, she and Toby made a great creative team. I felt sorry for her a bit because I was doing the cooking for everyone and so all my meals revolved around meat, meat, and more meat, poor old Susan was vegetarian and I can’t actually remember her eating anything the whole ten days. She would have paid big money for a lettuce.

Susan, Toby and Ben communicated really well and as the whole focus was on helicopters and mustering, Ben and Rankin didn’t disappoint. Their aerial work was breathtaking, and Ben really got into the whole film thing. He was actually coming up with great ideas for shots and where to put the camera and what angle and stuff. He was proving very artistic, in an outback type of way. Obviously under that tough, rugged, exterior was a sensitive creative new age guy.

Jane Atkins reminded me of the ‘Holy Spirit’, she was everywhere at once. Unstoppable and three months pregnant, she was the rock of Gibraltar. Jane has such a calm beautiful nature, whether it be out in the hot sun assembling the camera crane, or curled up in front of the computer like a cat, watching over everyone. Technical Assistant Jasper Montana was running around like an unregistered dog, tirelessly helping where he was needed and never complained. Sound man Ian Grant was the total professional as well and spent many hours following cattle around, taping their every bellow.

The only drama was when a Jet Ranger helicopter fitted with a special Cineflex camera that the BBC had hired looked as though it wasn’t going to make it. This caused a bit of concern as the special Cineflex camera was crucial to the whole thing. But Jane, after numerous phone calls and emails, and with a little help from God, made it happen.

After days of filming Ben and Rankin doing their wild manoeuvres in the choppers, and cattle wheeling to and fro through the scrub, it was time for the grand finale. It was time for the big money shot. Two thousand head of disgruntled beef had to be brought in and yarded up. It really was a great spectacle and all the many hours of planning really came off. With the Jet ranger and the Cineflex camera high up in the sky taking in the whole vista, Ben and Rankin set about driving the mob into the yards in their dragonfly-like mustering choppers. Through a veil of dust the choppers weaved, pitching, diving, steering the frenzied mob in towards the yards. On the ground were horsemen and motor bikes turning back any beast that tried to head back to the scrub. Toby Strong of course was courageously right in amongst it all getting some of the best shots I’ve ever seen. Ian Grant, camouflaged in the trees, captured some great sound and everything went off brilliantly. The BBC had won the day!

With the cattle yarded, big bustling Ben Tapp landed and rolled himself a well deserved smoke, it had been tough, but all in a day’s work when you’re a legend.

Next day was the completion of the filming. After a humongous party that night, it was time to pack up all the kit and head back to Darwin to get the film crew on the plane. There was many a teary eye and a hazy hangover as we all said our goodbyes. Friendships were made and it really had been a special time. Whether we ever see each other again who knows?

But one thing I know for sure, the Northern Territory will never forget the day the BBC came to the ‘Outback’.

Saharan Love Affair?

by Jane Atkins, Researcher, Deserts and Grasslands

My love affair with the Sahara started last year when I was looking for the most impressive and beautiful place to film people searching for water in the desert. Like any love affair, the last few months have seen me totally in love with the Sahara, telling everyone about it, then the next moment immensely frustrated, tearing my hair out and cursing it, never wanting to go back!

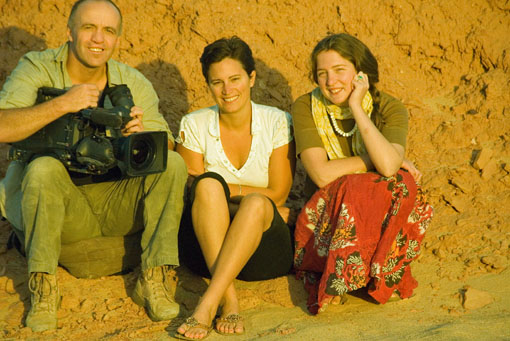

Here I am with our guide, Hamdi

The story starts back in March when I started looking into desert wells. Essential to life in the desert, wells are found in every desert known to man, but one passionate Italian geologist whispered down the phone, ‘I can tell you the best place of all.’ As the UNESCO consultant on desert areas, he had seen more sand dunes than I could imagine, so I was keen to hear his words of wisdom. ‘Algeria’ he said. Hmm.. not somewhere I had ever wanted to go, but who knows.. I might be surprised.

So a few weeks later I was on a plane to Algeria, and then flying from the capital, Algiers, to a small town called Timmimoun. From the window of the nearly empty plane, all I could see was desert- golden dunes, then stretches of flat hard baked desert rock, big escarpments and dried out river beds snaking through the emptiness. We flew for three golden hours and still the desert stretched on. I hardly saw a soul down there, a few small towns in the middle of nowhere, but that was it. How on earth do people live here? And why?

This was my recce, my first visit to Algeria and this extraordinary part of the Sahara. From the moment I stepped into the heat and saw the dunes I was in love. It was magical. And when I saw the desert wells, I was astounded. I had never seen anything like this. There was not just one well or two here in the desert, but hundreds and thousands. Individually they looked like huge mole hills, but in a long line this lunar landscape looked as if it had been blasted by a bomber plane. Amazingly, some of these wells were 600 years old and the system they are based on dates back to 5000 years ago. Incredibly, even today these wells and passages are still the only source of water for some people here.

I took photos, recced other locations, met people who dig these wells, and others who farmed small gardens in the desert. I wrote shot lists and planned how to reveal this incredible landscape and tell this story. A week later I was back in the office and writing applications to Algerian officials to get permission to film and import a hot air balloon for aerials. That was back in May. Between then and my Algeria shoot I was filming in Kenya but Algeria was always on my mind.

But as the shoot got nearer, I was beginning to tear my hair out. My Production Co-ordinator (the lovely Isabelle Corr) and I had written more letters and filled in more paperwork than I care to recall. I was hoping that Algeria would welcome a filming project revealing its extraordinary natural heritage, but there were so many hurdles to cross, I wasn’t sure I wanted to go back!

At the end of August we finally received our filming visas, and then the unimaginable happened. The wonderful sound recordist I was hoping to go to Algeria with, died in a tragic accident. I could not believe it. He was so full of life and energy. Filming out there would not be the same without him. And then a week later, the safety climber we were supposed to be taking also had a serious but not fatal accident; falling from a cliff while climbing. With only three weeks to go until the shoot, we had to find new crew and get them visas in quick turn around time.

Then there was another blow. Sadly, one very important bit of our kit was refused. We were not allowed to bring in the hot air balloon. I had hoped to film aerials over the Algerian desert, giving a spectacular bird’s eye view of these strange and ancient wells, and the beautiful villages and gardens but, despite providing every insurance document and licence, the authorities said No. Dany, the hot air balloon pilot, who shot beautiful aerials of the Niger desert for us last year, was as disappointed as we were but so as not to risk the rest of the shoot, we had to cancel that aspect of the filming project.

It is now November and I am back from Algeria. After the rollercoaster summer preparing for the filming trip, I can say with huge relief that we did finally get ourselves and our kit into the desert. Under the 45 degree heat of the Sahara, the team managed to build a climbing rig over the wells to lower our cameraman 15 metres into the desert rock, where it was cool, dark and quiet. Our great cameraman (also an expert caver) Gavin Newman managed to squeeze through the tiny manmade passages to film Mafourdi, a sweet 70 year old man, nimble as a 17 year old, as he descended to meet him in the darkness.

From the surface I stared nervously into the dark hole. I could hear tapping and rocks falling as more rock was drawn up in buckets. Communicating by walkie talkies, I blindly suggested shots to the cameraman, as it was too tight for me to go down inside the wells too. As I tried to focus on getting the shots to tell the story, I tried not to think of tales I’d been told about passages collapsing, trapping workers inside in dark desert graves. Luckily this was not our fate. You’ll have to watch the Deserts film to see the whole fascinating story but for now, all I can say is that thankfully this rollercoaster ride ended well, and give a huge thanks to the team - Isabelle, Gavin, Willow, Sam, Said and the Ba’amar guys - for all their hard work!

A Year on Human Planet

by Willow Murton, Assistant Producer, Oceans/Jungles team

9th October 2009

This time a year ago, I flew to La Paz in Bolivia, the highest capital city in the world and there, short of breath and cheeks full of Andean colour, I began life on the Human Planet team. I type this blog now under the stifling heat of the Algerian Sahara, many miles from those early cool heights.

Sometimes it is good to stop and reflect. There has not been much time over the last year for moments to look back – so much looking forward into the matrix of kit lists, itineraries and budgets that the months and the countries can go by.

This October evening, we gathered on a carpet outside under the date palms and the eager gaze of the local well workers who we have been filming with. Swirls of white turbans and the excited movement of children surround a small screen as we play out clips of what we have filmed over the last few days. They watch the images and the sounds they have patiently repeated in order to get just the right shot, in the right light. They laugh and we relax. This is one of the best moments of film-making, sharing the work of crew and contributors. We hope all our ridiculous demands make some kind of sense when seen on screen, and we too begin to understand more as questions bounce between us.

The claustrophobia of the small tunnel where we have been filming opens out into the warm evening. Small glasses of sweet mint tea are passed about amongst the comments. Filming is a demanding and long process which the workers have participated in with huge patience and good humour. In order to give them a glimpse of how the final film may come together, as well as a chilly insight into another underground world, we put on an edit from an Arctic sequence. There we are, warm in the evening air, watching people wrapped up from icy cold. There are gasps when I say that the temperature there is thirty degrees below Celsius. The days here in the desert are usually thirty degrees above and not unusually much higher. Beneath the arid surface of the Sahara, the workers here have dug through thick red clay to make tunnels to feed an ever-growing irrigation system. They cannot believe the effort of these distant Arctic dwellers as they dig into frozen crevasses. They are even more incredulous when they realise why. What the Inuit consider a gastronomic delicacy, the workers of the Sahara struggle to imagine edible. The frozen walls of an igloo protecting those inside from the cruel cold of the Arctic belong to another world, far from the rich red buildings of this small village, where people seek shade from a relentless burning sun.

Yet, further North, the Arctic is beginning its own dark turn to the winter once more. This year on Human Planet has spanned continents and captured moments of incredible feats, emotion and beauty. As the workers leave to sleep before they are called to prayer again and back to their work, I contemplate a year which has taken me to a frontline in the Simien mountains, above Greenlandic glaciers, into the path of avalanches, under sea ice and onto its floe edge, from Arctic darkness to midnight sun, from the green of a desert oasis to the barren hillsides of a Caribbean island. Like the Andean heights where I began, it takes my breath away.

A Grass Calendar

Jane Atkins, Researcher, Deserts/Grasslands team.

A waving white flag is usually a sign for peace, but in the Omo valley it was quite the opposite. In a vast valley of green grasslands and leafy trees these bright flags stood out as bold signs announcing that a violent stick fight was being planned between two villages. It was these incredible stick fights, or Dongas that we hoped to film - but finding out exactly when they would happen was a bit trickier! With only a ten day shoot in this massive valley that stretched to Sudan, we had to find out when each Donga was taking place, and if the chiefs of each village were happy for us to film.

White flags waving

Luckily we were working with Zablon Beyene, an incredible person and wonderful fixer, who introduced us to wise old chiefs and proud confident warriors with smiles.

Zablon and I share our umbrella

Over a 5 day recce we walked through villages and valleys to meet Suri elders, sat under shady trees in the heat of the day to talk to young fighters, and sketched out a badly drawn and dusty map of which villages were planning Dongas.

Sitting on the grass, with my map in my dirty hands, we just needed to mark it according to our western agenda of time. Diary planning and meeting deadlines becomes second nature in TV, but here dates were less clear, even to Zab! When we asked the chief when the Donga would happen he picked a long stem of grass, and with dark, leathered hands and tied evenly spaced knots. He explained how each knot represented one day, so the grass stalk handed to us with 8 knots meant the Donga would be on the 8th day. With slight apprehension I translated the dates onto my map, and thanked the chief. Now, after hundreds of handshakes and Suri meetings, all that remained was getting the camera crew to the right location.

The knotted rope calendar

On the morning of the Donga we walked to the clearing - it was silent, except for the sound of hundreds of dragonflies buzzing around in the sun! 2 hours later, with all our camera kit ready and a crane rigged, we looked at the empty clearing and hoped we’d got the right day after all!

We heard the men coming before we saw them; chants and songs through the trees, getting louder as they approached. Then gun shots! This, Zablon told us, was just guys firing shots into the air to psych themselves up. It worked, as the air was suddenly filled with excitement and adrenaline, as hundreds of men poured into the clearing, waving their sticks. As the crowd circled two posturing fighters, they stabbed a white flag into the ground; the donga had started.

To set the scene our cameraman Mike Fox moved the crane 20 feet into the air to reveal an amazing image of hundreds of men in combat - a scene you’ll never see any where else. We filmed all day, with the crane, then moving hand held amongst the crowds and spectators, and also with an incredible high speed HD camera that captured the force of each fighter. Moving through pumped up crowds, dodging swiping sticks, and ducking from celebratory gun shots were part of the experience and chances we took to film the sequence.

As I led a cameraman into another position I was mistakenly hit by one stick, and as I ran for a new battery I heard the whizzing of a gunshot past my head! The brutality of the Donga really did separate the men from the boys, and was a fascinating insight to the Suri world. As we packed up I was happy that all our planning had paid off, but even happier that we’d all survived!