The Original Jungle and its Mighty Beasts

By Rachel Kinley, Assistant Producer of Human Planet

The word Jungle itself comes from the Sanskrit word for forest. It was in this original jungle, on the borders between India and Burma, that we filmed people working with one the most iconic of jungle animals – the forest elephant.

It took us three days and several forms of transport, including a rickety old logging truck, to reach the camp which would be our home for the next two weeks. There wasn’t just us staying there though, this camp was home to a dozen elephants and their mahouts.

We were there to film them moving felled trees from the forest, as part of a sustainable logging business. Watching the elephants at work was so impressive. They are powerful beasts who can move a massive log as if it was a tiny twig. Amazing!

Being so strong, they really intimidated me at first. After we’d filmed with them for a while though, I realised that that their mahouts were well in control of these animals. So, when I was offered the chance, I jumped at the opportunity to take one for a ride. I was only allowed to travel on the female elephants so as not to spook the bulls. Our cameraman Robin however was game to ride any elephant any which way, and even learnt how to steer it along with his feet!

Spending time with these mahouts who dedicate their lives to looking after these animals was an empowering experience. This sequence really shows that the Human Planet Jungles programme isn’t just about living in rainforests, it’s about the incredible relationships people have with their environment and the species which live within.

The Human Planet Jungles and Grasslands episode can be seen on the Discovery Channel.

Little Human Planet

by Elen Rhys, Producer, Little Human Planet

When delightful Dale Templar told me that Human Planet had been commissioned, my brain immediately started working overtime. Waw, what a great opportunity for a children’s spin off on CBeebies. Surely, if they would be filming humans in far flung and remote locations around the world, they were bound to be meeting children too. What a unique chance to work alongside this huge landmark commission to create something special for the BBC’s youngest viewers. And basically, that is how the CBeebies commission, Little Human Planet came to be.

Little Human Planet is a little sister series to Human Planet. It consists of 16 x 5 mins programmes that will be broadcast during the same period as the main series – but of course, at a time when 3-6 year olds are at their most attentive.

It’s a simple idea with a simple format. Each programme follows a typical activity in the life of a child from around the world – a glimpse to a CBeebies viewer of how their counterparts live, wherever they may be. On reflection, an unspoken celebration of what makes children different and what makes them the same in a colourful and often surprising voyage of discovery.

Unfortunately, I didn’t get to pack my passport to film the sequences. This was done by the brilliant Human Planet location teams. Yes, we liaised closely together regarding style and vision, understanding that certain things like nudity or blood and gore couldn’t be used. Naturally, this proved difficult in certain locations where few clothes, if any are worn and hunting for food is the norm. I was never sure what I was going to get, only crossing my fingers they would meet some children and film some magic moments . I’m used to having a bit more control, so this was quite difficult for me but I soon realised I needn’t have worried.

Each time a team came back with special Little Human Planet labelled footage it was like the anticipation and excitement of opening Christmas present. Who would, Dan Young, my editor and I meet this time? Could it be Dua, a six-year-old girl who lives in a tree house in a jungle in Papua or mischievous four-year-old, Carlos Eduardo, who lives on the flooded banks of the Rio Negro? Or how about four-year-old Shoree helping her dad build a ger home in Mongolia, or three-year-old Edjongon, who walks long distances each day to collect water from a well in Mali? Even though I have never met these fascinating characters, I feel as if I know them. And though the children’s experiences, circumstances and environments differ hugely, I learnt that at heart children are all the same and their smiles are universal.

Yet, paradoxes come to light. Without generalising, many of these children and families have very little, but yet, seem contented where community and sharing is a way of life. It taught me a lot and got me thinking..As a mum to a six-year-old, have we in the Western world lost our perspective ?

I am honoured, grateful and proud to be a tiny part of the Human Planet family and I hope there will be more opportunities like this in the future. If so, can I please come next time?

Dale Templar - Series Producer

Here’s hoping - Elen!

Little Human Planet is one of spin-offs programmes and extras that are part of the Human Planet . We have already had a post from our team at BBC, Radio Three working on Music Planet and in a few weeks we’ll have one from our BBC Learning team. They are using our footage to make programmes that will be used as teaching aids in scools.

Music Planet

by Roger Short, Producer, BBC Radio 3

The Music Planet team – engineer James Birtwistle, Andy Kershaw and producer Roger Short – look at the wrong camera while on the job in Papua New Guinea

Yes indeed, as Andy Kershaw tells us on his promo video, filmed recently in Papua New Guinea, he and Lucy Duran are currently travelling the globe for a new eight-part series of world music programmes. Music Planet will be a companion series for BBC One’s major new natural history project Human Planet, presenting the music of some of the cultures featured in the TV series.

As I write, Andy is on his way to Thailand, there to join producer James Parkin and engineer James Birtwistle for a trip that includes Laos and Burma; tomorrow Lucy Duran and I, with engineer Martin Appleby, head off on a rather shorter haul to Galicia in northern Spain - this is for a feature on how the local traditions are influenced by music from across the sea (and did you know there was a mass migration of Britons buying villas in northern Spain in the sixth century, bringing Celtic culture to that part of the world?).

Just as Human Planet shows how people relate to their landscape and environment, in Music Planet, we’re showing how all this is reflected in the local music. So far Lucy has visited Madagascar, Kenya, Greenland and Mali, and Andy has been to the Solomon Islands as well as Papua New Guinea. There’s plenty more before the series broadcasts early next year. If you’re interested, we’ll let you know how we get on…

Masters of the jungle

by Willow Murton, Assistant Producer, Oceans and Jungles team

There are places that you imagine you may return to and people you may meet again and then there are farewells to people and places you assume you will hold as a treasured memories. For me Aurelio village was one of those places; so remote, so distant, one of only two communities where the Matis of Brazil live. Set in the vast indigenous Vale do Javari reserve, it takes several days’ boat ride to reach the village, as well as many months of painstaking preparation. I had first come here to make the series “Tribe” and couldn’t believe my luck when I was asked to make a return trip for “Human Planet”– a rare privilege.

There is good reason to return to this remote corner of the Amazon for Human Planet’s Jungles episode. The Matis are true masters of the rainforest. Pete, our endurance fit cameraman, and I are reminded of this on our first filming day. An hour into the hunt we’d come to film, we are up to our knees, even thighs at times in swamp mud, soaked through by the unrelenting rain and all eyes on deadly poisoned darts being fired over our heads! Pete turns to me and asks if it’s all going to be like this?

Luckily it isn’t. Thank goodness, our second hunt is on firmer, drier ground. We follow the hunters into their world, immersed in the sounds and signs of the forest as we track monkeys in the canopy. For all the planning, there are still situations that happen which are unimaginable and that can never be relived. After many hours hunting with no success, we are about to give up when suddenly a troop of monkeys scatters across the trees. The hunters follow, taking aim in the tree tops. The camera’s eye is no match for the trained focus of the hunters. They find their mark fast and before long, they are tying dead monkeys together to carry them back through the jungle. Exhilarated by the speed and skill of our forest guides, we head back to camp just as the rain starts to fall.

Part of our return journey is by boat. There we sit, the two of us, blowpipes and cameras balanced on benches, monkeys at our feet and a group of hunters devouring the last of the snacks that we brought. Survival in the jungle is about taking the opportunities that it offers – and a camera crew’s rations are as fair game as anything else found in the canopy. Pete turns to me, waving the sandflies from his eyes, and he utters the words no traveller should speak: “Imagine if we got stuck here now”.

At that moment the boats motor clunks and we are indeed stuck – the hungry hunters and us up an Amazonian creek with no paddle! The boatmen, calm as ever, are quick in their evaluation of the situation. The motor is beyond repair but we are not beyond help. Bushe, the Matis translator who I also worked with four years ago, turns to me and instructs me to use the satellite phone to contact the village to arrange a rescue. It will be long soggy bug filled few hours before anyone can reach us. We ask Bushe what they would do without the BBC’s technological intervention. ”The forest has everything that the Matis need”, he replies and every Matis knows the paths that winds through the forest to the village.

This is Tupa. She guards and administers frog poison rubbed into the hunters' arms to purify them before the hunt

We cover ourselves in insect repellent and lie back on the roof of the boat in beautiful resignation to the sunset and our eventual rescue. What passes in the next few hours is one of those gifts of disguised fortune – stolen time and experiences. Floating across the river, the boatmen set nets and within minutes, they have gathered a dozen fish for supper including piranha. Soon, we are back on the bank, in front of a bright fire, stabbed with sticks of fresh fish. We joke around the flames, laughing into the smoke. The fish is quickly eaten with the bizarre addition of fruit flavoured rehydration salts for those who prefer their piranha on the tropical tasting side.

Then we all wash in the river, as our socks dry on sticks over the embers. Laughing still, we clamber back onto our boat. The sunset darkens to a thick sky studded with stars and the sounds of the forest once more. Somewhere in the distance, a motor can be heard but for the moment, the jungle absorbs us entirely. It is so good to be back amongst my Matis friends.

Contact is Complicated

By Rachael Kinley, Researcher, Oceans and Jungles team

There have been a few times when people, and their stories, have really choked me up on location. Often it’s in interviews, when I get the chance to ask people about their lives, motivations and past experiences. The anthropologist in me loves this pause amongst the frenetic requirements of filming, being able to linger in the moment, and ask personal questions that wouldn’t come up in day to day small talk.

My most recent interview was with Pikawaja, a member of an Awá-Guajá community living in Maranhão, Brazil. Many of the people in this community were first contacted by the outside world in 1980, but some members of the village were only reached as little as three years ago. Since contact, it’s been quite a rapid, and sometimes rocky, process of assimilation. FUNAI and the government have given them motorboats, television, a satellite dish, running water, refrigerators, cattle, horses, a health clinic and schooling.

Although at first daunted and perplexed by the stark and dramatic alterations to their lives, most Awá-Guajá now seem excited by the change. Signs of the influence of wider Brazilian society are visible all over the village; children play by acting out scenes from Rambo, teenage boys sport bleached-orange mohawks and girls have started to pluck their eyebrows. However, the Awá-Guajá are in an odd situation where they are offered tastes of the world outside their reserve, but are discouraged from leaving to embrace these wholeheartedly.

Although at first daunted and perplexed by the stark and dramatic alterations to their lives, most Awá-Guajá now seem excited by the change. Signs of the influence of wider Brazilian society are visible all over the village; children play by acting out scenes from Rambo, teenage boys sport bleached-orange mohawks and girls have started to pluck their eyebrows. However, the Awá-Guajá are in an odd situation where they are offered tastes of the world outside their reserve, but are discouraged from leaving to embrace these wholeheartedly.

The childhood play and image-consciousness may be what’s seen on the surface, but I learn more about the increasingly complicated and more personal aspects of how the contact process has directly affected Pikawaja’s life.

Our interview begins slowly, following several relocations due to intrusive sounds from cockerels crowing and a pet howler monkey in desperate need to relieve itself. Once we reach a quiet spot, we (Pikawaja, myself, Willow Murton, who’s recording the sound and Antonio Santana, a linguistic graduate student who’s our key to Pikawaja’s thoughts) settle down to begin. As she starts, the softness of Pikawaja voice catches me off guard. When she speaks, she talks in stories, recounting events in a language where dialogue simply begins, without contextualisation.

Luckily Antonio is a master of the Guajá language and knows how to steer Pikawaja off one story onto another, to elucidate further information without breaking her flow. Her voice is quiet yet she doesn’t stutter or falter in her responses. Only once, she pauses mid-flow as her eyes glance to acknowledge her husband at the window behind me. He’s eager for Pikawaja to finish so that they can go hunting, but she stays to finish her stories. When he leaves, she recommences.

Pikawaja says that she was a young girl when the white people came and brought her family from the forest. She tells tales of gunfire and being scared that she would be killed. Without any change of tone discernable to my ear, she tells us of the personal tragedy of contact. After the white people came for them her parents developed a fever. With no medicine effective in treating the new diseases they were exposed to, they both died. She lost both parents and a brother.

Later, when Willow and I read through the translation, we are both hit by a wave of sadness. We retire early to our hammocks and painful thoughts spin around our heads. Pikawaja is now back in the forest, at a hunting camp, where she feels far happier and at home compared to village life.

Later, when Willow and I read through the translation, we are both hit by a wave of sadness. We retire early to our hammocks and painful thoughts spin around our heads. Pikawaja is now back in the forest, at a hunting camp, where she feels far happier and at home compared to village life.

Pikawaja’s is not an unusual story. Louis Forline, a leading anthropologist on location with us, who was worked with the Awá-Guajá for almost 20 years, tells me that the first Awá community to be contacted lost 75% of its members. It was mainly the elders who died, until they started to build immunity to common diseases. The Awá-Guajá have now been left with a very young demographic. With so few elders around, and a sentiment of looking to the future, their chosen village leader, who sports a fetching orange Mohawk, must barely be out of his teens.

There are now just under 400 Awá-Guajá remaining in the world. It’s estimated that around 60 of them are still uncontacted and live in the forests around where we were filming. They are currently in danger from poachers, miners, loggers and cattle ranchers who have accessed their territories and are ransacking parts of their reserve. And with part of the Carajás Mining venture’s 910km railway running along their doorsteps they really are feeling the squeeze. While FUNAI, the Brazilian government’s National Foundation for Indians, has a policy of not contacting Isolated Indians, there is talk afoot that it may be in the best interests of these last true forest dwellers to integrate them into a village, perhaps even the one we’ve been filming in.

After my interview with Pikawaja I can now start to imagine what it will be like for these uncontacted people who still live nomadically in the forest, if they too are thrown into a world of horse riding, action movies, film crews and the common cold.

The issues go far deeper than I can begin to summarise here. As Indian policy in Brazil is in a constant flux, Louis believes that prospects for the Awá-Guajá future are hanging in the balance. He’s keen to raise awareness of the Awá-Guajá and their current situation; hopefully our programme will prompt further recognition of their lives. FUNAI and healthcare organisations are among those working hard for the welfare of the Awa-Guaja, but they do not always have all the resources they need.

It’s a complicated tangle being played out amongst Amazonian groups - how to balance the changing influential factors in life and identity amidst an ever-changing set of attractions and influences.

Ground Control (to PD Tom!)

by Joanna Manley, Production Coordinator, Jungles/Oceans team

Being the Production Coordinator on the Jungles and Oceans team means I’m responsible for sending Tom, Charlotte, Willow and Rachael to Jungles and Oceans all over the world. I seem to be in a constant state of organised chaos and even though I get left behind with the damp life jackets and lingering smell of the Jungle whilst the team flies off to the next amazing destination, I love my job and my team.

I have several time zones set on my phone which I continuously update as teams leave, come back, move on and go out again. It’s sometimes difficult to keep track of where everyone is and invariably they all phone at the same time (usually just as I’m trying to get some lunch!) needing a new camera, flights changed or just someone back in reality to talk to when they’re in the middle of a wet jungle with broken kit and infected feet!

On Human Planet we’re often dependent on people and animals being the same place at the same time when the conditions are right. This is how not to do it….

We had;

Jon in Indonesia trying to film a Whale Hunt close to two earthquakes

Charlotte trying to film a shark whilst there was a tsunami warning for the area

Willow in Bristol trying to track Hurricanes to film in the Caribbean and there weren’t any

Tom and Rachael leaving for the Philippines to live on a boat for 7 days in the midst of the worst typhoon season the Philippines have seen in years.

How typical!

With so many shoots going off and coming back and with heaps of kit needed, our office has got a reputation for a being a bit of a muddle. Danny who delivers post to our office says he has nightmares about it and grumbles it’s like an assault course trying to get from one side of the room to the other. To be honest he’s right, especially as there is a camouflage theme to a lot of the objects such as hammocks, tarps, tents and thermarests. We’ve got wetsuits and life jackets hanging off the back of the door, waterproof bags and jungle ponchos in a heap behind my desk with a solar shower perched on top and on Tom’s desk at the moment is a pile of coconut shells used to call sharks in Papua New Guinea.

My two sets of desk drawers are filled with all sorts of things not usually found in an office drawer…

Muddy batteries from the jungle

Leaking bottles of anti mosquito repellent

Boxes of antibacterial hand wash

A box of latex gloves for covering radio mics

Several dead Central African Republic bees

A tangle of 4 way plug adaptors and extension leads

I’ve got a heap of tapes, gaffer tape and loose cable ties all over my desk and a pair of size 12 flippers along with three Mauritanian jilbabs the team wore whilst filming in Mauritania to the side of my drawers.

Even though I don’t get to see the places we’re filming in person I get a good idea of what’s it like there even before I see the footage. From the smells emerging from their kit bags when they get back, to the sound of pouring rain and bugs I hear in the background when I’m talking to them on the Satellite phone.

You need a sense of humour in this job! Here I'm wearing wooden goggles from Bajau divers and a lifejacket, next to some shark-calling coconuts

Our next shoot is going off to Brazil on 8th January so we’re battling through our Christmas party hangovers to get everything packed up and ready so we can take a much needed break before another crazy year on Human Planet starts!

The Breast of Friends

By Rachael Kinley, Researcher, Jungles/Oceans team

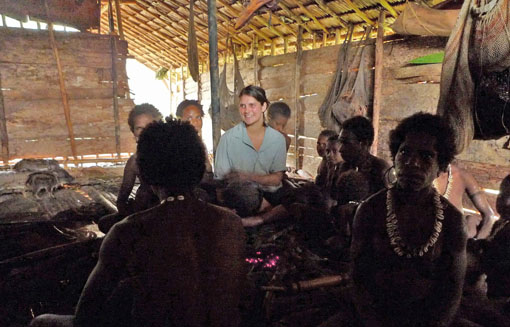

Before filming begins, it’s important to spend time with the contributors without big cameras in their faces. It helps to strike up a friendly rapport and make the future weeks more productive and enjoyable for all. So, our first day in Papua with the Korowai is spent in their home, a tree house.

Making friends in the treehouse

Korowai houses are communal and split into male and female sides, to avoid furtive touching in the evenings. So, as the rest of the crew, including the translator are men, I sit down with the women, while the crew all head outside to take in the view from the male balcony.

Friendship forming begins inside the house. In the UK, we’d receive cups of tea and cake, here it’s fire-charred lumps of sago palm, fresh from the flames. We start making net bags together, rolling lengths of rattan along our thighs, entwining the fibres to form a string which is then plaited together to create a bag that is strong enough to hold up to 70kg.

Whilst we are winding, I try to spark up a conversation. But with Jim, our translator, out of sight this gets to be a bit tricky. I only know one word in their language, and they know none in mine. I begin by pointing at items around us and learning the words for their shell necklaces, pet pig and net bags. After we’ve exhausted everything on their person, the tables are turned and they start pointing and teaching me words for parts of my body - hair is ‘habianto’ and breast, ‘am’. They seem to be extremely intrigued by my breasts.

A couple of children reach over and prod them. The older women giggle, encouraging the girls on. The next thing I know, they start to unbutton my shirt. The Korowai are both amazed at the lifting properties of my Gossard Superboost bra. They begin to imitate its effect by cupping their own breasts in their hands with curious looks. It feels slightly surreal to be sitting, metres up in a jungle tree house, being communally undressed by several women and children. I help them to unfasten the clasp and the women stroke my breasts, smiling, giggling, repeating am am am.

It’s lovely, it’s touching, we laugh together and are definitely bonding. But amidst all this, my mind is thinking why couldn’t this be at the end of the four weeks in the jungle when I’d definitely be much thinner…. I guess that you can take your clothes off in the jungle, but it’s harder to get your head out of the UK.

Fumble in the jungle

by Tom Hugh-Jones, Producer/Director - Oceans and Jungles team

I know that working on Human Planet is supposed to be a dream job and don’t get me wrong, I love what I do, but it doesn’t half try your nerves sometimes. This is definitely not the right career path for those who suffer from stress and nothing proves my point better than my recent experiences of filming in Jungles. I’m sure some people will disagree, but for me this has to be the most challenging environment to work in.

For a start the weather is just too unpredictable. Ok, so you know it is going to rain, but you don’t know when or for how long. Every day we seem to be in a never ending cycle of setting up kit ready to shoot, only to have to pack it up again as the next rain storm passes by. Rain is an ever-present menace, but it’s the 100 % humidity that causes the serious problems. Not only does it make for unbearably sticky working conditions, it also has the habit of rendering our equipment totally unusable. Our extremely expensive camera lenses constantly fog up, making it look as if everything’s being shot in a misty 70s dream style. No big deal, an hour of clenching the lens in the warmth of your groin area solves that issue. The light is better now anyway and god knows what the tribe is doing, but it looks amazing…..OK, let’s shoot! But wait, not so fast! what’s that flashing red light on top of the camera? Oh yeah, that’s the humidity warning and now our only option is to pack the camera body away in a hot-box for a day to drive out the condensation. Well, never mind, there’s always tomorrow.

Drying the camera in the sunshine

After a wet night we get up ready for action, only to find that now there’s an even more serious technical issue that’s beyond the cameraman’s fixing abilities. This is when the next jungle challenge presents itself. Jungle locations are invariably very difficult to access, making communication with the outside world close to impossible. When things break, trying to get replacements sent in usually means sending some poor local person off on a three day hike to the nearest village to meet an aeroplane we’ve had to charter at great expense.

Everyone waiting

It isn’t just kit that falls apart in the forest; it’s the crew as well. Rain and sweat combine to ensure your clothes and shoes are never truly dry and pretty soon the rot sets in. Any minor cuts from the myriad of spikes and spines you inevitably encounter soon becoming gaping septic wounds. And to top it all there’s the constant assault from leeches, ticks, mosquitoes and all sorts of other unidentified parasites that are after your blood. With every daily wash I seem to discover a new colony of animals that have chosen to make their home on my body.

Insects attack

Each time I go on a trip in the rainforest, I swear I’ll never do it again, but somehow I keep on finding myself coming back for more. After I’ve got back home, slept in a proper bed, had about ten baths, been to the doctor to get my various tropical infections treated and then put in my insurance claims for all of our broken cameras; I begin to realise it is all these trials that make for my most cherished memories of filming for Human Planet.

My latest trip to film with the Korowai tribe of West Papua was a perfect case in point. We had all the usual battles with the elements, technical glitches and medical mishaps but having the opportunity to spend time with this tribe was perhaps my most amazing filming experience ever. Although their culture is about as far as you can get from our western world, the Korowai welcomed us into their lives with amazing warmth and it was just incredible to see how they managed to live such rich lives with nothing but what they found in the forest. What’s more I think we got a pretty stunning sequence but you’ll have to judge for yourselves when Human Planet comes out in 2011.

Korowai Children

Dale Templar - Series producer, Human Planet

I have no real idea what Tom is moaning on about! He’s clearly not been in the UK enough this summer. Based here in Bristol most of the time I am beginning to wonder if we’ve been secretly transported to the tropics. I’m finding it impossible to plan anything outdoors; lots of crazy unpredictable rain, some of it torrential; lots of bugs (swine flu is rampant). The only big difference is that it’s so cold and I hate the cold. Summertime in the British urban jungle is not without its frustrations!

Welcome to Human Planet

Dale Templar, Series Producer

by Dale Templar, Series Producer

So what is Human Planet? Human Planet is a new 8×50 minute landmark documentary series being made by BBC Television. The series celebrates the human species and looks at our relationship with the natural world by showing the remarkable ways we have adapted to life in every environment on earth. It is due to be transmitted in the UK in the New Year 2011 and will be rolled out across the world soon after.

The production team is split across two sites, one in Bristol and one in Cardiff.

In BBC Bristol we are part of the world renowned Natural History Unit. You may have heard of us, but if not, you’ve probably watched some of our programmes. Many have been presented or narrated by Sir David Attenborough, like Planet Earth and Blue Planet. Most recently we’ve just finished Nature’s Great Events which our own executive producer, Brian Leith, worked on.

BBC Human Planet : Simien Mountains

BBC Wales, based in Cardiff, are probably best known in the UK right now for producing high end popular dramas like Doctor Who. Torchwood, another sci-fi doc that comes out of Cardiff, is also an HD production and Human Planet will be using the same excellent post-production facilities. The factual department is best known for its ground-breaking anthropology documentary series Tribe.

In total we have a core team of 20 phenomenally talented programme makers, who come with a wide range of skills and experiences. Working with us are some of the best wildlife and documentary camera crews and fixers in the world. For the first time we have a dedicated stills photographer, Timothy Allen, who will be posting his own Human Planet blog every week at http://timothyallen.blogs.bbcearth.com/

BBC Human Planet : Suri stick fight

The series started in full production in the summer of 2008 and we will be shooting over 70 stories in some of the most remote locations on earth in around 40 different countries.

Each episode will focus on one single environment: desert, jungles, arctic, grasslands, rivers, mountains, oceans and urban. Many of the stories are extremely dramatic and will show how we have successfully adapted and survived in the most challenging places on the planet.

As from next week each member of the team will be blogging their stories from the Human Planet. I will keep you updated on where everyone is and give you general news about the series.

Currently, we have teams that have just come back from the remote southern region of Mongolia, filming for the desert episode. On location are the Jungles and Mountains team who are in the Central African Republic and Nepal. I’ll let you work out which team is where!

BBC Human Planet : Arctic Dawn

That’s it for now …enjoy the photos and the sneak preview from the series. See the link if you’d like to read what Timothy Allen’s been up to and don’t forget to explore the new BBC Earth site too. Look out for the regular Friday posting from the Human Planet team, with fascinating stories and tales from both our many locations and from the office.