Contact is Complicated

By Rachael Kinley, Researcher, Oceans and Jungles team

There have been a few times when people, and their stories, have really choked me up on location. Often it’s in interviews, when I get the chance to ask people about their lives, motivations and past experiences. The anthropologist in me loves this pause amongst the frenetic requirements of filming, being able to linger in the moment, and ask personal questions that wouldn’t come up in day to day small talk.

My most recent interview was with Pikawaja, a member of an Awá-Guajá community living in Maranhão, Brazil. Many of the people in this community were first contacted by the outside world in 1980, but some members of the village were only reached as little as three years ago. Since contact, it’s been quite a rapid, and sometimes rocky, process of assimilation. FUNAI and the government have given them motorboats, television, a satellite dish, running water, refrigerators, cattle, horses, a health clinic and schooling.

Although at first daunted and perplexed by the stark and dramatic alterations to their lives, most Awá-Guajá now seem excited by the change. Signs of the influence of wider Brazilian society are visible all over the village; children play by acting out scenes from Rambo, teenage boys sport bleached-orange mohawks and girls have started to pluck their eyebrows. However, the Awá-Guajá are in an odd situation where they are offered tastes of the world outside their reserve, but are discouraged from leaving to embrace these wholeheartedly.

Although at first daunted and perplexed by the stark and dramatic alterations to their lives, most Awá-Guajá now seem excited by the change. Signs of the influence of wider Brazilian society are visible all over the village; children play by acting out scenes from Rambo, teenage boys sport bleached-orange mohawks and girls have started to pluck their eyebrows. However, the Awá-Guajá are in an odd situation where they are offered tastes of the world outside their reserve, but are discouraged from leaving to embrace these wholeheartedly.

The childhood play and image-consciousness may be what’s seen on the surface, but I learn more about the increasingly complicated and more personal aspects of how the contact process has directly affected Pikawaja’s life.

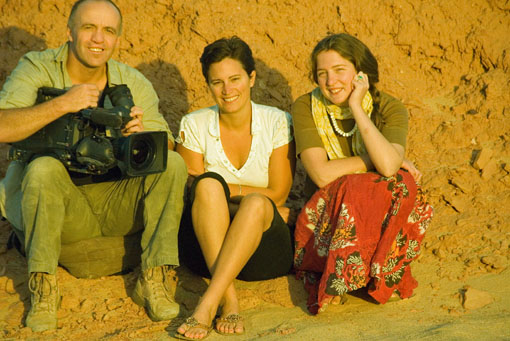

Our interview begins slowly, following several relocations due to intrusive sounds from cockerels crowing and a pet howler monkey in desperate need to relieve itself. Once we reach a quiet spot, we (Pikawaja, myself, Willow Murton, who’s recording the sound and Antonio Santana, a linguistic graduate student who’s our key to Pikawaja’s thoughts) settle down to begin. As she starts, the softness of Pikawaja voice catches me off guard. When she speaks, she talks in stories, recounting events in a language where dialogue simply begins, without contextualisation.

Luckily Antonio is a master of the Guajá language and knows how to steer Pikawaja off one story onto another, to elucidate further information without breaking her flow. Her voice is quiet yet she doesn’t stutter or falter in her responses. Only once, she pauses mid-flow as her eyes glance to acknowledge her husband at the window behind me. He’s eager for Pikawaja to finish so that they can go hunting, but she stays to finish her stories. When he leaves, she recommences.

Pikawaja says that she was a young girl when the white people came and brought her family from the forest. She tells tales of gunfire and being scared that she would be killed. Without any change of tone discernable to my ear, she tells us of the personal tragedy of contact. After the white people came for them her parents developed a fever. With no medicine effective in treating the new diseases they were exposed to, they both died. She lost both parents and a brother.

Later, when Willow and I read through the translation, we are both hit by a wave of sadness. We retire early to our hammocks and painful thoughts spin around our heads. Pikawaja is now back in the forest, at a hunting camp, where she feels far happier and at home compared to village life.

Later, when Willow and I read through the translation, we are both hit by a wave of sadness. We retire early to our hammocks and painful thoughts spin around our heads. Pikawaja is now back in the forest, at a hunting camp, where she feels far happier and at home compared to village life.

Pikawaja’s is not an unusual story. Louis Forline, a leading anthropologist on location with us, who was worked with the Awá-Guajá for almost 20 years, tells me that the first Awá community to be contacted lost 75% of its members. It was mainly the elders who died, until they started to build immunity to common diseases. The Awá-Guajá have now been left with a very young demographic. With so few elders around, and a sentiment of looking to the future, their chosen village leader, who sports a fetching orange Mohawk, must barely be out of his teens.

There are now just under 400 Awá-Guajá remaining in the world. It’s estimated that around 60 of them are still uncontacted and live in the forests around where we were filming. They are currently in danger from poachers, miners, loggers and cattle ranchers who have accessed their territories and are ransacking parts of their reserve. And with part of the Carajás Mining venture’s 910km railway running along their doorsteps they really are feeling the squeeze. While FUNAI, the Brazilian government’s National Foundation for Indians, has a policy of not contacting Isolated Indians, there is talk afoot that it may be in the best interests of these last true forest dwellers to integrate them into a village, perhaps even the one we’ve been filming in.

After my interview with Pikawaja I can now start to imagine what it will be like for these uncontacted people who still live nomadically in the forest, if they too are thrown into a world of horse riding, action movies, film crews and the common cold.

The issues go far deeper than I can begin to summarise here. As Indian policy in Brazil is in a constant flux, Louis believes that prospects for the Awá-Guajá future are hanging in the balance. He’s keen to raise awareness of the Awá-Guajá and their current situation; hopefully our programme will prompt further recognition of their lives. FUNAI and healthcare organisations are among those working hard for the welfare of the Awa-Guaja, but they do not always have all the resources they need.

It’s a complicated tangle being played out amongst Amazonian groups - how to balance the changing influential factors in life and identity amidst an ever-changing set of attractions and influences.

Where are the Fish?

by Rachael Kinley, Researcher, Oceans and Jungles team

Of the three months that I’ve been on location for Human Planet Oceans shoots, over half of this time has been spent waiting for fish to appear. Off the shores of three continents, from sunrise to sunset, we’ve searched the open seas desperately hoping for some ‘sign’ that they are on their way.

First it was waiting for migrating mullet in Mauritania. The idea was to film with the Imraguen people who inhabit the Bank D’Arguin National Park and fish the huge numbers of mullet that pass through their waters each year. Every day for two weeks we optimistically headed out to sea in the fishermen’s dhows, but the mullet never arrived. Was it the moon, the wind or the water temperature? We will probably never know but after much debate we reluctantly decided to call off the shoot.

Then we moved on to Laguna on the coast of southern Brazil to try again to film a similar story. It was hard to decide when was the best time to go as the local fishermen seemed to have wildly conflicting ideas of when the mullet season actually occurred. In the end we embarked on our trip in mid May and although at first it looked as if we were going to be unlucky for a second time, after spending three weeks on location we finally managed to film fishermen hauling in impressive numbers of fish.

OK, so we were successful, but it was touch and go for quite a while and I swore I would never go on another shoot that depended on fish turning up. But what do you know, this October I was off again on another wild fish chase. This time it was off the coast of Palawan in the Philippines, sailing for fourteen hours a day for seven days with deep sea diving fishermen desperate to land a big catch. Sitting out at sea on a boat in the tropics, overlooking palm tree fringed sandy beaches, is not the worst place in the world to be left in limbo, but after days on end of no filming opportunities and burning our budget, even paradise can lose its appeal. But as so often seems to be the case on Human Planet shoots, on the very last day we finally managed to net something spectacular enough to make the cut.

We had what we needed, but I was dismayed to hear that even this catch was half the size of those that the fishermen said they used to get. The problem was not that the people had been lying to us about when and where the fish come in, nor that they had lost their traditional skills, but that there are no longer plenty of fish in the sea. Although newspapers and documentaries such as End of the Line tell us that global fish stocks are declining, as we still see plenty of fish on our supermarket shelves, it is all too easy to ignore the warnings.

I myself was aware of the problem, but it was really brought home to me by witnessing first hand how barren the seas of the world have become. At first the persistent lack of fish on our shoots seemed little more than the annoying bad luck that can plague any film shoot, but talking to people whose lives and livelihoods depend on maritime resources, I have become increasingly aware that diminishing fish stocks are becoming a huge problem affecting millions, if not billions, of people around the world. Having seen just how hard the lives of some of these people are already, I hate to think how they will survive if the fish disappear altogether.

Dale Templar - Series Producer - Human Planet

Heartache for Haiti

About six months ago, I sent assistant producer Willow off to do a recce in Haiti. We were looking for a place to show the huge destructive force of hurricanes and Haiti is regularly caught in the path of the worst storms that sweep through the Caribbean. Ironically, we never filmed in Haiti; in the 2009 season the hurricanes chose other paths. It was a bitter-sweet failure for the series. Willow and I were both aware we’d wasted time and money but also felt secretly pleased that the people of Haiti had escaped yet more devastation and destruction for another year. We could never have imagined the cruel twist of fate that would hit them just months later. Of all the places on Earth for a earthquake of this magnitude to hit. On her trip , Willow was given an insight into the desperation, poverty and hopelessness faced by the majority of the Haitian population. Hours after the earthquake, she and I talked on the phone, both unable to take in the enormity of the disaster. She had been there, I had made films after the Kobe Earthquake in Japan and in Banda Ache following the Boxing Day Tsunami. The hearts of the Human Planet team go out to the people of Haiti. Maybe, just maybe, something good will come from this.

Arctic Awakening

by Bethan Evans, Researcher, Arctic and Mountains team

I’ve recently returned from my last Arctic filming trip for Human Planet. My amazing year and a bit in the North culminated with an encounter with a majestic animal known as the King of the Arctic.

The shoot was in the town of Churchill which is also known as the “Polar bear capital of the World”. The town is built near to an ancient polar bear migration route. Each autumn polar bears gather nearby, waiting hungrily for the sea ice to reform so they can get back out to their hunting ground. Forced onto land during summer due to the melting ice the bears have not eaten anything substantial for months. So who can blame them when they wander into the town enticed by the lovely food smells that are produced by restaurants or even the bins and rubbish dump!

We were there to film how people carry on their daily lives, when for several weeks of the year, there is a real possibility of coming face to face with the only land animal that is known to actively predate on humans! Luckily there is a specialist protection team set up in Churchill called the Polar Bear Alert. These guys work tirelessly, in the most unique way, to ensure that the both bears and people are safe and unharmed – watch the full story in Human Planet: Arctic programme in 2011!

The Polar Bear is an icon – a majestic animal that’s revered but also feared, a symbol of a lost wilderness. I felt so privileged to have the opportunity to see these incredible animals. So it was a shock when it finally dawned on me that my first chance to see a Polar Bear in the wild might also be my last. I’m so used to seeing images of the Polar Bear whether it be in Hollywood films, marketing campaigns for soft drinks or even Christmas cards. They somehow make these Arctic dwellers seem abundant but of course the sad fact is they’re not.

Climate change is causing a vast reduction in sea ice and therefore a loss of natural habitat for the polar bears which, in time, will lead to their demise in the wild. With this realisation I began to think of all the different Arctic people I have met on my Human Planet journey. If climate change continues at its current rate what will happen to them? How will Amos the Greenlandic fisherman make a living from fishing at winter ice holes when the ice isn’t thick enough to support him? How will Lukasi and Mary go under the ice to collect mussels when they can no longer predict how the ice will behave?

The Arctic people I have met are incredibly adaptive – their way of life has changed drastically in the space of one generation. Many people have the ability to take the best from western technology and adapt it to work with traditional knowledge. However, Arctic peoples are inextricably connected to the landscape - a change in their environment impacts on every aspect of their lives. This isn’t something that is going to happen in the future, it is happening right now.

The good news is that it’s not too late to slow down or prevent the negative impacts of climate change not only for Arctic Peoples and animals, but for all of us. Small measures from you and me can make all the difference. Take a look at these two BBC sites for more information http://www.bbc.co.uk/climate/ and http://www.bbc.co.uk/bloom/

Making this series has really raised my awareness of the incredible variety of cultures and wildlife that the Earth sustains. I hope that if I can change my ways the first time I see a polar bear won’t be my last and the environmental impact on Arctic peoples lives will be minimal.

A Year on Human Planet

by Willow Murton, Assistant Producer, Oceans/Jungles team

9th October 2009

This time a year ago, I flew to La Paz in Bolivia, the highest capital city in the world and there, short of breath and cheeks full of Andean colour, I began life on the Human Planet team. I type this blog now under the stifling heat of the Algerian Sahara, many miles from those early cool heights.

Sometimes it is good to stop and reflect. There has not been much time over the last year for moments to look back – so much looking forward into the matrix of kit lists, itineraries and budgets that the months and the countries can go by.

This October evening, we gathered on a carpet outside under the date palms and the eager gaze of the local well workers who we have been filming with. Swirls of white turbans and the excited movement of children surround a small screen as we play out clips of what we have filmed over the last few days. They watch the images and the sounds they have patiently repeated in order to get just the right shot, in the right light. They laugh and we relax. This is one of the best moments of film-making, sharing the work of crew and contributors. We hope all our ridiculous demands make some kind of sense when seen on screen, and we too begin to understand more as questions bounce between us.

The claustrophobia of the small tunnel where we have been filming opens out into the warm evening. Small glasses of sweet mint tea are passed about amongst the comments. Filming is a demanding and long process which the workers have participated in with huge patience and good humour. In order to give them a glimpse of how the final film may come together, as well as a chilly insight into another underground world, we put on an edit from an Arctic sequence. There we are, warm in the evening air, watching people wrapped up from icy cold. There are gasps when I say that the temperature there is thirty degrees below Celsius. The days here in the desert are usually thirty degrees above and not unusually much higher. Beneath the arid surface of the Sahara, the workers here have dug through thick red clay to make tunnels to feed an ever-growing irrigation system. They cannot believe the effort of these distant Arctic dwellers as they dig into frozen crevasses. They are even more incredulous when they realise why. What the Inuit consider a gastronomic delicacy, the workers of the Sahara struggle to imagine edible. The frozen walls of an igloo protecting those inside from the cruel cold of the Arctic belong to another world, far from the rich red buildings of this small village, where people seek shade from a relentless burning sun.

Yet, further North, the Arctic is beginning its own dark turn to the winter once more. This year on Human Planet has spanned continents and captured moments of incredible feats, emotion and beauty. As the workers leave to sleep before they are called to prayer again and back to their work, I contemplate a year which has taken me to a frontline in the Simien mountains, above Greenlandic glaciers, into the path of avalanches, under sea ice and onto its floe edge, from Arctic darkness to midnight sun, from the green of a desert oasis to the barren hillsides of a Caribbean island. Like the Andean heights where I began, it takes my breath away.

Haiti and hurricanes

by Willow Murton, Assistant Producer, Oceans/Jungles team

Leaving Haiti I say my goodbyes and hope that I don’t visit the people that I have come to know again this year. For the first time after a recce, I really do hope that I don’t come back. Because if I do, it means the people of Haiti will have been hit yet again by a destructive storm.

The calm after the storm - Gonaives, Haiti

For many people, Haiti is synonymous with violence, gun fire cracking over destitute slums, the sound of voodoo drums, a dark mysticism. When I said that I was coming here, some friends looked at me with envy and said that they had always dreamt of going on holiday to Tahiti. Those who heard right looked at me with curious interest and concern. Their eyes were full of the preconceptions that spring from a country whose history begins for many with disease and exploitation. More recently, it has been written by the devastating statistics of its poverty and the language of disaster in the face of social unrest and tropical storms which have hit the country. And so I set off, with the envious gaze of the mistaken and the worried glances of the better informed.

Passenger on a bus in Port-au-Prince

Recces are one of the best parts of this job. You get to be professionally nosey and personally privileged in places that you would never visit otherwise. This is certainly one trip that I would not have imagined making and it still does not feel real until the doors of Port-au-Prince airport open. The tensions and aggressions that I expected to meet me in the Haitian capital are nowhere to be seen. I am struck by the apparent calm, masked in the chaotic bustle of the traffic and roadside. A bored UN policeman, a check point on a road dented with potholes, intercut with colourful tap-tap pick-ups crammed with people. Whilst I have a glimpse of the reality of life about me, I too am on the sidelines, looking out at the passing world. This feeling comes back to me time and time again on the trip. Perhaps it is the distance between the cool air-conditioned rooms of the hotels where we stay at night and the hot, dusty shacks that we visit in the day.

Boys standing on flooded salt ponds

The shoot however will be an immersion, literally. Following a family through a storm and following floods is not something that is easy to plan. I have become an amateur storm chaser, scouring weather charts and learning the grammar of waves and wind. For all the guidance that I am given, there is no way to predict the track of the storms with any certainty. Had there been a way, the people of Gonaives would surely not have found themselves so unprepared for the four storms that struck the town last year, bringing deadly floods and taking lives and homes.

Devastation in Gonaives after last year's floods

Mountains of dusty rubble dug from the houses still sit in the streets, flanked by blocked canals, lottery stalls and the wrecked shells of cars. At the edge of the ocean, a small group of fishermen gather, making boats and talking, as children and pigs run about amongst piles of empty conch shells. A little boy flies a kite, made from a plastic bag, over a cluster of ramshackle huts. On a door, the words “Site Ana” are sprayed. The settlement is new, named after the storm, Hurricane Hanna, that took the previous homes of the settlers. Children swim in the pools of water beyond, around the ruins of a building she flooded. Crude fishing boats sail out over former salt plots. Life continues in the remains of the storms.

A flooded house a year after last year's floods

There is an inevitability to the fate of the people who live here which is openly admitted. It is disarming. They have no choice but to stay, to adapt, to reclaim the small spaces of land, the snatches of life that they can. Last year, the families in some corners of Gonaives spent months living on roof tops. Neighbours who had houses with two storeys offered shelter to those without. Fear, loss and finally survival were shared under stormy skies. I still have no idea what story we will be able to tell this year but I hope that it is one which finds that same strength of humanity in the eye of a storm I pray never comes, even if the cold statistics say it will.

Dale Templar - Series Producer - Not so Natural Disasters

When Willow came back from Haiti last week and showed me the photos of Gonaives I was instantly transported back. I have location directed two films telling the stories of the aftermath of what we call a “natural disaster”. The first was the 1995 Kobe Earthquake in Japan. The second was the more recent tsunami, where I filmed in Banda Ache in northern Sumatra, the place where quarter of a million men, women and children perished. Like Haiti, Ache was already classed by the BBC as a “hostile environment” even before the disaster. As I travelled from the airport, which was inland and relatively untouched, we headed towards the coast. Soon the twin natural forces of both a powerful earthquake and the massive tsunami waves started to reveal themselves. I was prepared for the earthquake ruin, I’d seen so much in Kobe but I wasn’t prepared for the scene as I neared the coast. A few months earlier this had been a packed fishing community. Well over a kilometre from the sea shore, there was nothing, just nothing. The ocean had taken everything. When I saw Willow’s recce material the memories of Ache came back, I understood her confusion and disbelief.

It’s called a natural disaster for good reason but when you see it for yourself there is something so viscerally un-natural about it. Somehow it just isn’t right, isn’t possible. On both occasions I was telling the story of the people who had against the odds survived the very worst nature could throw at them. You come away with an insight into two of the great strengths on this Earth, the force of nature itself and the power of humanity.

It’s a Small Small World…

by Nicolas Brown, Producer/Director, Arctic and Mountains

“Is one of you Mr. Brown?”

Shock, blood rushes to my face. “Who knows me here? This is the most remote airport I have ever been to. (Have I done something wrong…?)”

We are in Ummannaq, which is nearly 600 km North of the Polar Circle, halfway up the West Coast of Greenland. The town sits on a tiny island (12 sq km) dominated by a towering rock called “Hjertefjeldet”, or Heart–shaped Mountain. It is easily the most picturesque fishing village I have ever seen - and the most far flung.

Ummannaq and Hjertefjeldet

The woman in front of me laughs at my bewildered look. “My husband is Ole Jørgen Hammeken. He is friends with your father.”

Soon I am seated across from Ole Jørgen — the man my father calls “The Eskimo Errol Flynn”. The comparison is apt. Ole Jørgen has a stage presence that fills a room. A decade ago, he led my father on an expedition to the northernmost mountain in Greenland, now dubbed Hammeken Point. Ole is the first native Greenlander to be honoured as one the world’s elite explorers.

I'm on the left, Ole Jorgen on the right

We laugh at the coincidence — Ole has been to my home thousands of miles away in Gypsum, Colorado, in the heart of the American Rockies. There he ate venison that we harvested from the forest behind our house. Now, totally unplanned, I am seated at his table, eating halibut harvested that morning from beneath the Ummannaq sea ice.

Weeks later, Human Planet takes us to Nepal. It is another place I have never been. Once again, I am greeted with a shock.

“You look like your brother…” muses a Nepali man standing before me. “But he is a strong climber—strong as a Sherpa. Are you?”

Pemma Sherpa

I stare into the beaming, mischievous smile so characteristic of Nepali Sherpas. A flash of recognition hits me. Put goggles on his eyes, an oxygen mask on his face—yes, it is Pemma Sherpa, who led my brother to the top of Mt. Everest last year. I’ve seen the pictures (it was my brother, Michael Brown’s, fourth successful summit).

Michael Brown

I can tell that Pemma is going to push me. I’m not the mountaineer my brother is. I curse myself for not training harder for the expedition ahead…

When I started work on Human Planet I knew we would be exploring places I’ve never been before. But I never expected to keep bumping into people I know! In the famous words of my fellow countryman Walt Disney, “It’s a small, small world!”

Dale Templar, Series Producer - Icebreakers

Last week we had unfermented mud in Mali stopping a shoot, this week we’ve had sea ice breaking up far too fast in Greenland. Pushing complex filming trips back at the last minute is not ideal but bringing them forward can be a total nightmare and that’s exactly what it has been. Whether or not you believe the global warming theories, things ain’t what they used to be in the Arctic. One morning last week our “Queen of the Ice”, Bethan Evans got the call she never wanted from North-East Greenland. Overnight a big storm had come across the region and many kilometres of sea ice had been literally blown away - the team had to come and film “now!”, not in four weeks time as planned. With director Nick Brown away in Nepal (see above), the camera crew and safety co-ordinator booked to work elsewhere and flights every two weeks at best, we were starting from scratch. Willow Murton, our assistant producer had to drop the other story she was working on in Siberia and it was Arctic action stations. Somehow, I do not know how , we have an amazing team on location with one of the world’s top Arctic cameramen, Doug Allan. He had another shoot pencilled in for the series Frozen Planet that got cancelled due to weather! How lucky was that?

Deadly Darts and Rotten Bamboo!

by Charlotte Scott

Assistant Producer, Jungles/Oceans team

As one of a team of four working on the Jungles episode of Human Planet, I said “yes” without any hesitation when asked if I’d like to take a colleague’s place at the last minute and go to Colombia. On this recce, a research only trip, my task was to go and meet the Emberá tribe based deep in the jungles of Colombia. The Emberá in this region are the last actively known group of people to still tip their blowpipe darts with poison frog venom.

It was only after looking into the whole trip in detail that I realised how much of a challenge this recce could be. The jungle is always a difficult place to work in and if I injured myself I would at times be seven hours away from the nearest help.

It all started with a bang before I got anywhere near the jungle. On my first night in Bogota I was uncomfortably close to a large car bomb that killed two people close to my hotel. So I was only too happy to set off for the jungle the next morning. Two days and a 4 ½ hour mule ride later we arrived at our village in the heart of the Chocó Mountains.

- A muddy mule ride

I then had to explain to all the men in the village that I was interested in seeing the process of finding the frogs, making the darts and going on a hunt with them. They were happy to help but first they told me of their malnutrition problems and the lack of electricity and trained health workers and asked if I could tell their story.

The next morning after the first obligatory rain shower (this is one of the wettest places in the world… 13.3 metres p.a.), we set off into the jungle on foot. Around 2 hours later ,after slipping and sliding along vertiginous and muddy paths, we stopped for a well earned rest at a dilapidated hut. Whilst taking a breather, we heard calls from above to say that some of the hunters had found poison dart frogs. They do this by calling to the frogs at certain times of the day until they call back, then they track them down in the undergrowth by following their calls.

- I’m the tall one at the back, along with the fixer, Juan Pablo Morris and the amazingly skilled Embera hunters: Jorge, Elieser, Guillermo, Elias, Boutilio, Alfredo, Eduardo, and a few others

I proceeded to film how they transferred the poison from one black-legged poison frog to around 60 darts. This process is only carried out by the hunters once every 6 months to a year as the poison is so potent that it lasts for over a year.

As I was filming the transfer of poison onto the darts, my foot found a bit of rotten bamboo and went straight through. The vibration through the floor caused all the darts to dance in the air. I held my breath, but luckily they all landed safely without scratching anyone…… Just one scratch from a tipped dart would have meant instant death.

———————————————————————————————

Narwhal Alert - Dale Templar, Series Producer

It has been all systems go this week on the series. We have had to go into over-drive to get an extremely difficult shoot off to the north of Greenland to film an extraordinary sequence involving Narwhal. Bethan Evans, the ice queen of Human Planet, discovered that the sea ice has started to break up much sooner than expected. Hunting Narwhal is extremely difficult and one of the key hunting times for a particular community in the far north-west ties into the ice sheet melt. Everyone is looking pale and there are boxes of kit everywhere. The team is rallying around as ever and top Arctic camerman Doug Allan is falling off one frozen trip and straight on to another!

Singing in the Rain

by Mark Flowers, Producer/Director Rivers/Urban team

The most heart-stealing and downright soul- enhancing benefit of working on a Human Planet shoot is the children we encounter while we are filming. It’s unbelievably refreshing to step outside of a regulated, fast-paced and impersonal modern, urban society and meet people who live in a more open, communal and for me personally, a far more “Human” way.

The children we met during our trip to film living root bridges in one of the most remote areas of North-East India were fantastic - cheeky, smart and funny.

To the young people who live in isolated hill villages in the rainforests of Meghalaya, the arrival of a gangly bunch of giant, pale-skinned strangers, brandishing weird black boxes, screens and cables, was the most surprising thing to happen in a long while. The circus had come to town!

Within minutes of us stepping out of the cars, there were bright eyes at the windows and small hands waving from the homes we passed. High pitched “hellos” echoed all around while tiny toddlers stood dumb struck for a few seconds in doorways and then exploded into howls. Dogs barked and sulky, caged cuckoos crooned from dark corners.

Whenever we set up to film very quickly we were surrounded in a small lava flow of children, far to shy to talk to us individually, but en masse, well that’s different, isn’t it? Whenever we got the camera out we were mobbed!

- Smiling to camera

The funny thing was that we were hoping to shoot short stories for our sister production, working title “Little Human Planet”, showing how children live in different parts of the world. This depended on the little people we were hoping to film behaving as if the camera wasn’t there: Fat- chance!

We soon realised that if we were to get any shots that looked even vaguely natural, the crowd of children needed to be distracted, and that meant entertaining them. Guess who had to do the entertaining: Me. Yikes!

Just so you know I am a greying man in early middle age. I am not a totally serious person but as a director on location I have a role to play out, a reputation to maintain. I have to be seen to be in charge! Usually you’d find me in earnest conversation with the team, or looking sternly down my monitor checking that each shot is right.

Singing in the rain

I didn’t have a white rabbit, I don’t know any tricks, so the only thing I could think of to do instantly was to sing! it was raining too , I had an umbrella – so I started with “I’m singing in the rain” but soon moved on to nursery rhymes to keep the “show” on the road.

I am not sure if the footage of the crowd and the children will end up being used as everyone looks very surprised or is laughing, but the most magical thing is that the little children joined in with me. Incredibly in such a remote part of the world they knew “Baa Baa black sheep” and “Twinkle Twinkle little star”! The memory of singing in the rain with little children holding technicolour parasols is a memory I will always cherish.

Here is a clip. Unbeknown to me, Richard our cameraman turned the movie camera on me and caught me during my act. Enjoy!

[bbc-bc video=21316429001]

Sperm Whales

Whale hunting in Indonesia